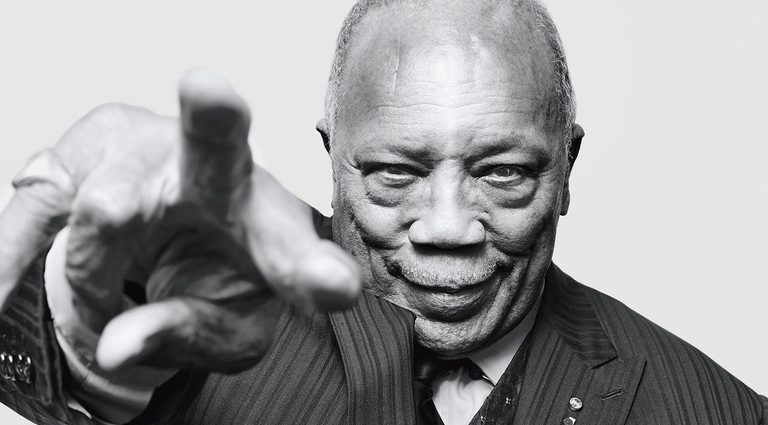

Quincy Jones Has a Story About That

So he begins. He begins talking about his life. It’s a life punctuated by so many disparate encounters and achievements and circumstances that it is hard to believe they are the experiences of a single man. There is a lot of talking to do.

There is the career, of course: the jazz musician, the arranger, the record executive, the soundtrack composer, the solo artist, the producer of the biggest pop album in history, the entrepreneur, the media magnate, the film and TV producer, the philanthropist…and on and on. Jones is one of just a handful of people who have accomplished the EGOT—winner of at least one Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony. (1) But these seem almost trivial and incidental alongside the actual life he’s lived.

For one thing, he seems to know, or have known, everybody. When Jones says that he “lost 66 friends last year” and begins to list recent departures—”David Bowie, George Martin…”—it’s more than an acknowledgment of some recent rough years. It’s also a testament to his unique gift for not just knowing people but also sharing unforgettable moments with them. Someone once compared his omnipresence to Forrest Gump’s; Jones has heard this one, but he prefers a further twist on it: “the Ghetto Gump.”

He worries often that he’ll say too much (“I always get in trouble, you know. My daughter Kidada calls me LL QJ—Loose Lips”), but it doesn’t really seem to stem the flow. And because each sentence from his mouth comes out sounding like a benediction, it takes a while to register that the word the 84-year-old Quincy Jones uses more than any other, as a term of both endearment and opprobrium, is motherfucker. In fact, he will say it in my presence 89 times.

Mostly we talk about the past, naturally, and we get there soon enough. But it’s characteristic of his spirit that as he sits down he is already telling me about his present and his future: “I never been this busy in my life. We’re doing ten movies, six albums, four Broadway shows, two networks, business with the president of China, intellectual property. It’s unbelievable, man.” He tells me about all the celebrations planned for his 85th year: a Netflix documentary, a prospective ten-part TV biopic he hopes will star Donald Glover, a star-studded TV event on CBS that he tells me Oprah will host.

I guess you’re supposed to be the one to slow it down.

“Never. ‘Cause I don’t think like that.…I stopped drinking two years ago. Because I had diabetes 2. And it’s the best thing I ever did. My mind’s so clear now, you know. And the curiosity’s at an all-time high.”

Do you wish you’d done it sooner?

“Yeah, but I came up with Ray Charles and Frank Sinatra, man. (2) I didn’t have a chance. Seven double Jack Daniel’s an hour. Get out of here. Ray Charles, Frank—those guys could party. Sinatra and Ray Charles, them motherfuckers invented partying.” Jones shows me the ring on his little finger. Sinatra, he went on, “wore that for 40 years. When he died, he left it to me. This is his family crest from Sicily.”

You wear it every day?

“I can’t take it off.”

And you think of him?

“Yes sir. I love him. He was bipolar, you know. He had no gray. He either loved you with all of his heart or else he’d roll over your ass in a Mack truck in reverse. He was tough, man. I saw all of it. You know, I’d see him try to fight—he couldn’t fight worth a shit. He’d get drunk, and Jilly, his right-hand guy, stone gangster, would get behind him and break the guy’s ribs. Man. What memories. We had a good time, though. We’d do one-nighters, I’d fly with him on his Learjet, he said, ‘Let’s get on the plane before Basie’s drummer’s cymbal stops ringing.…’ Six Playboy bunnies on that.”

Should I ask what happened next?

“No. It was fun, man. Always been fun. You gotta enjoy life.”

You and Frank Sinatra had the first song played on the moon, didn’t you? (3)

“Yeah, 1969. Buzz Aldrin. Frank knew first and he called me up, and he was like a little kid: ‘We got the first music on the moon, man!’ He said, ‘We’re putting it back in the show!'” (4)

I believe he made you scrambled eggs once?

“Yeah. I was in Dean Martin’s studio at the Warner Bros. lot, writing music for Sinatra at the Sands, and I got locked in for the weekend. He came in on Monday morning, said, ‘Hey, Q, how do you like your eggs?’ Miles (5) said the same thing, on a different occasion, at the Chateau Marmont. But that was just a coincidence.” He smiles. “They say coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous.”

And how were the Miles Davis eggs?

“Good. Both of them were fantastic. Frank could cook, man. His pasta—shit!”

Is it true that you can cook the best lemon-meringue pie?

“Right. You put some lime in the meringue. I love to cook, man. To me, it’s like orchestration. Like, what’s the most prominent instrument in the symphony orchestra? The one that you always hear? Piccolo. And when I cook, I cook like an orchestrator. Lemon rules, man. Lemon knocks out hot sauce, garlic, onions, everything. Shit, I’ve got some great dishes, man. I cook gumbo that’ll make you slap your grandmother. Oprah (6) had my Thriller (7) ribs on the show four times.”

Why are they called Thriller ribs?

He shrugs amiably. “Oprah dramatizes everything.”

With his big band in Vienna, 1960.

Photo Credits: FRANZ HUBMANN / IMAGNO / GETTY IMAGES.

“Look where we’ve come,” he says, raising his eyes to the ceiling. “From wanting to be a gangster to…all the other stuff.”

Jones spent his early years on the South Side of Chicago. His mother was taken away when he was 7—”to a mental home,” he says, “for dementia praecox.” His father, also called Quincy Jones, worked as a carpenter (8) for, as his son now puts it, “the most notorious gangsters on the planet, the Jones boys.” It was rough and scary, and the only promising option that a young boy living within it could envision was becoming a gangster himself: “The ’30s in Chicago, man. Whew. No joke. If you think today’s bad… As a young kid, after my mother was taken away, my brother and I, we saw dead bodies every day. Guys hanging off of telephone poles with ice picks in their necks, man. Tommy guns and stogies, stacks of wine and liquor, big piles of money in back rooms, that’s all I ever saw. Just wanted to be that.”

How old would you have been when you first saw a dead body?

“Seven or 8 years old. Fucking South Side of Chicago, they don’t play, man. Harlem and Compton don’t mean shit after Chicago in the ’30s—they look like Boys Town to me. Chicago is tough. There’s something in the water, man.”

And you assumed you’d become a gangster, too?

“Hell yeah. I wanted just to have a comfortable life, man. Because it was frightening, and every day you never knew what was happening. That’s what you wanted to do so you could protect yourself. Or that’s what you believed. It’s bullshit. It was a terrible way to live, you know. Seven years old, I went to the wrong neighborhood, I didn’t know the codes and stuff. Big gangs on every street.”

And what happened?

“Oh, they grabbed me, and they took a switchblade knife and nailed my hand to the fence right there.” He points to a scar he’s had on his hand for 77 years. “And they stuck an ice pick”—he points to his left temple—”in here, the same time.”

Did it hurt?

“Did it hurt? Fucking right it did! A switchblade in your hand nailed to a fence. Shit, man. And an ice pick here. Fuck, man, I thought I was gonna die. I was terrified. Because you feel helpless. And then Daddy came out finally and hit ’em in a head with a hammer.”

We are interrupted by a man named Michael who earlier had welcomed me into the house. “You need anything?” he asks. “I’m gonna send up some stuff. You need a drink or anything?”

“Some girls,” Jones replies.

“Will do,” says Michael, clearly joking. He disappears, and Jones’s attention returns to me.

“You married?”

Yes.

“I’m not.” He laughs. “I got 22 girlfriends.”

You serious?

“I was married three times, man. Was told not to marry actresses or singers. I ended up with two actresses, Peggy Lipton and Nastassja Kinski (9), and a superstar model. I didn’t listen to all the advice.” He laughs again.

You really have 22 girlfriends?

“Hell yeah. Everywhere. Cape Town. Cairo. Stockholm—she’s coming in next week. Brazil—Belo Horizonte, São Paulo, and Rio. Shanghai—got a great girl over there from Shanghai, man. Cairo, whew.”

They all know about each other?

“Yeah, I don’t lie. And it’s amazing—women get it, man. Don’t you ever forget they’re 13 years smarter than we are. Don’t you ever forget it.”

Can I ask how old the youngest one is, and the oldest one?

“Well, my daughters gave me new numbers, because they kept saying, ‘Dad, you can’t go out with girls younger than us.’ I said, ‘Y’all are not young anymore.…’ So the new numbers are 28 to 42. They gave them to me.” (10)

Would you ever go out with anyone your own age?

“Hell no!” Jones gives me a look, a kind of incredulity that is some mixture of horror and bewilderment. “You see me with an 84-year-old woman? Are you crazy?”

And why not?

“Why not??? Why? For what, man? There’s nothing…there’s no upside. You gotta be kidding. I got me some technology out there”—he gestures to the mansion’s perimeter—”that keep fat and old away from here. Buzzes if they’re too old. But you’d be surprised.… These women, the young ones, are aggressive now. Oh my God, they’re fearless, man. All over the world.”

Now, as you know, some people say that at a certain age the desire just evaporates.…

“Not to me. Hell no. Never.”

No sign at all?

He shakes his head. “Uh-uh.”

A few minutes later he shows me photos of some of his children: “When you’ve been a dog all your life, God gives you beautiful daughters and you have to suffer. I love ’em so much. They’re here all the time.”

How come you think you’ve been a dog all your life?

“I don’t know. Probably because I didn’t have a mother. And the big bands, that’s like the school of the dogs. Traveling bands? Every fucking night it was like the girls coming through Neiman Marcus: ‘Oh, I like trumpet players,’ ‘I like sax players,’ ‘I like guitar players’… Rita Hayworth, all of them. It was unbelievable, man. Frank was always trying to hook me up with Marilyn Monroe, but Marilyn Monroe had a chest that looked like pears, man.”

So you turned down Marilyn Monroe?

“Let’s not talk about it. Come on, man. We killed it. You know, I came up with the two wildest motherfuckers on the planet. Ray Charles and Frank Sinatra. Come on. They were good-looking guys, they had all the girls they wanted, and they showed you how to deal with it. So did Rubirosa—the king of the playboys. (11) Amazing man. What a guy. Eleven-inch dong. And in Paris to this day, you go to Chez L’Ami Louis, the waiter will come over to you with a pepper shaker and say, ‘Here’s your Rubirosa.’ He always used to say, ‘Quincy, it’s by the head, not the bed. Women give up pussy to get love, men give up love to get pussy.’ That’s the way it works. You know, all these women were available all over the world. I did a tour with Nat Cole in ’61 with my band—we couldn’t stop the girls. It’s incredible. Women are a trip, man.”

Do you ever wish you’d been a different way?

“Je ne regrette rien de tout. I don’t regret shit.”

Jones with three of his daughters, Kidada, Jolie, and Rashida, 1997.

Photo Credits: ALBANE NAVIZET/ KIPA /SYGMA /GETTY IMAGES;

Over the years, Jones’s explanation for why he is the way he is, and for all he has done in his life, has very often narrowed down to one single circumstance: growing up without a mother.

“For a son,” Jones tells me, “the worst thing that can happen to you is not to have a mother, man.”

His mother was a well-educated woman: “Boston University. Twelve languages, everything. She was amazing.” But she was not well. Much later in Jones’s life, there would be a diagnosis of what was wrong with her and she would find some kind of a cure, at least for her most extreme symptoms, and live until she was 94. But for a young boy, there was only the sense that something was very much not as it should be. In the past, Jones has spoken of an incident on his fifth or sixth birthday, when his mother took his coconut birthday cake and threw it, for no discernible reason, onto the back porch.

Did you have any happy memories of your mother before things went wrong?

“No. No, not one.”

When did you realize that she was troubled?

“Well, at that age it’s not so easily identifiable exactly what the hell’s wrong. But you can tell something’s wrong. My brother and I, we were 6 and 7 years old, we watched her taken away in a straitjacket. That’s tough, man. And we went out there to see her, Manteno State Hospital. Boy, that was heavy. When we first went in, there was a little blonde lady there, standing up with no shoes on, in her underwear, and she had a bowl of feces and she says, ‘You shall have no pie!’ I said, ‘God, let me out of there.’ “

I read that your mother did something awful, too.

“She went down and did number two.”

And then ate it?

He nods. “We were, you know, 7 years old. It doesn’t hit you that way it should hit you. On the way home, Lloyd said to me, ‘My brother, you shall have no pie!’ “

Even though, later, your mother recovered, you never really formed a bond with her?

“No. No, because you couldn’t trust her emotionally. Nothing you ever did was right.”

Was she proud of you?

“Yeah, but she was always sabotaging it. Always. She didn’t like me being in pop music. The first record I did with Dinah Washington—I was 20 years old or something—was ‘I Love My Trombone-Playing Daddy with His Big Long Slidin’ Thing.’ She didn’t like that. She didn’t want to know about that shit.” He laughs. “I don’t blame her.”

When Quincy Jones talks—wandering from subject to subject as he does—the next famous name is rarely more than a few seconds away, but it doesn’t seem like name-dropping or showing off. It’s as if this just happens to be the interesting world he occupies. So he’ll refer to the time Nelson Mandela tried to get him to touch a cheetah—”I couldn’t do it”—and then he’ll mention that Colin Powell called a couple of days ago because Powell was annoyed at how Tyler Perry appeared to be portraying him in a forthcoming movie. (Jones helped connect them.) Or he’ll refer to the time Steven Spielberg showed him the first abandoned prototype for E.T.: “They made that little monster, and he looked too much like a brother. That’s why the second one had blue eyes.” Or the occasion in May 2007, when Oprah brought Barack and Michelle Obama ’round to this house in an attempt, unsuccessful at the time, to woo Jones away from his friends the Clintons. “To try to sell me on them,” he says. “And we sat down in the kitchen, and for six hours…a really heavy meeting.” (12) As another aside, he’ll let slip that he saw Stevie Wonder last night: “Stevie and I are doing a lot of shit together.” Or he’ll say, pretty much apropos of nothing at all, “You run into amazing people—I’m thinking back to Norman Mailer, man. Shit, all those cats in New York. We used to just fuck up—ooh-là-là!” And smiles at memories that the rest of us can and should never know. Then he’ll gesture to the SpaceX model rocket across the room, over toward the library. “Elon Musk was my neighbor for ten years. Great guy, man. He’s a fearless motherfucker. Every week we’d have two or three dinners with Zuckerberg and Sergey Brin and all those cats. Jeffrey Bezos.” Jones makes a kind of exhalation noise. “Bezos—the richest motherfucker in the world now.”

He pulls out a book published a few years ago filled with photos and memories from his life, and he tells me about the time Bono invited him to come along to the Vatican in 1999 to meet Pope John Paul. “All the guys in the Vatican had these Vatican black shoes,” Jones recalls, but not the Pope. “He had on some burgundy wingtips, man, with thin tan rib socks, man. We had to go and kiss his hand before we left. And when I kissed his hand, I looked down and saw those shoes and it just fell out of my mouth. I said, ‘Oh, my man’s got some pimp shoes on.’ And he heard me.”

Isn’t that sacrilegious, telling the Pope he has pimp shoes?

“Oh, hell no. He’s just a man. I didn’t tell him.“

But he heard you?

“Yeah. When he died, I grabbed USA Today, and Bono said, ‘Quincy said he had some lovely loafers on.’ [Bono]’s a great guy. I stay at his castle in Dublin, because Ireland and Scotland are so racist it’s frightening. He said, ‘Trying, Quincy, to assimilate, but it’s not coming easy.’ So I stay in his castle.”

Jones exudes positivity about most of the people he has known, but not all of them, and he is not above Schadenfreude. When we meet, celebrity sexual harassers are falling like dominoes. Some clearly sadden him—he saw his friend Charlie Rose in Aspen the previous weekend—but others seem to offer him the satisfaction of justice served. Judging by how often he mentions it, the documentary Keep On Keepin’ On—which follows the friendship between the ailing trumpet player Clark Terry, who once mentored Jones, and a young blind jazz pianist, Justin Kauflin—is one of Jones’s recent projects that he takes the most pride in. It was shortlisted as one of the 15 documentaries up for an Oscar nomination, but it progressed no further. This is fresh in his mind, in part because he knows whom he blames for this disappointment.

“We almost won the Oscar, man. Weinstein double-crossed us with Citizenfour. He had both, but he double-crossed us. He was trying to get the one that he could sell the most, and Ed Snowden was the big topic then. But he double-crossed us, and I don’t give a fuck—see what happened to him?”

I ask him what moral he draws from this turn of events.

“That’s the higher power. That’s the way the higher power works. If there’s anything I’ve learned in 84 years, it’s that whatever you put out there, it will come back at you. That’s for sure.”

Even setting aside the improbability of a man rising out of his background to achieve all that he has achieved, there have been at least three specific moments in Quincy Jones’s life when it seems almost miraculous that fate allowed him to continue.

The first of these took place when he was 14 years old. The family had moved to Washington State four years earlier, and this change was the making of him: He discovered music, and he threw himself into learning it. Even if, at home, he was facing new challenges: “My stepmother was like Precious. Crazy bitch. And she didn’t call me by my name until I was 57. Said ‘Jones’s kids.’ ‘He’s upstairs playing that goddamn flute.’ It was a trumpet! She was a bitch, man. And she was illiterate. She beat the shit out of us every day. Every day.”

But he now had music to show him a path forward, a way out. He had learned the trumpet, taught himself arranging, and played with every band he could. One of these was part of the National Guard—Jones lied and said that he was 18 so that he could join. His friends did the same. “We used to go to Fort Lewis and Fort Lawton in the summertime,” he says, “and you’d smell the racism.”

That was how, one day, the five of them found themselves driving together in a car on their way to play at a rodeo in Yakima. “A little raggedy-ass car. Two up front and three in the back. I’m in the center. Trailways bus hit us. Everybody in the car died except for me. Reached up and pulled my friend, and his head fell off. That’s fucked-up for 14. It was very traumatic.”

Were you hurt?

“Little bit. I mean, the other guys were dead. His head fell off. I mean, I almost had a heart attack. See your friend with his head off? Shit.”

A couple of years later, Jones tried driving lessons. “I just couldn’t do it,” he says. Some days he was okay, but others he was all over the place. He says that his teacher eventually told him, “I don’t need another maniac out there,” and gave Jones his money back.

He hasn’t driven since.

On a soundstage with Frank Sinatra, 1964.

(Photo by John Dominis/ Time & Life Pictures/ Getty Images)

As Jones talks, a woman brings some food and puts it on the table. There’s various raw vegetables and dips and crackers. There’s also a bowl of sorbet, and that’s all that Jones touches.

When I arrived here this evening, Jones had just woken up. This is his normal schedule: Rise around four or five in the afternoon, and then ride through the night, his mind racing. He tells me he now speaks 26 languages. “I’m writing Mandarin, writing Arabic, writing katakana in Japan. I’ve been traveling all my life, and I guarantee I travel more than any motherfucker on this planet.”

You could really have a conversation in 26 languages?

“Try me.” He starts saying things in various languages I don’t speak.

What is that ability?

“I don’t know. It’s just natural.”

Many people of Jones’s age accept that their days may be coming to an end, and adapt accordingly. Jones is not one of those people. For the past eight years, he has spent six days a year at an exclusive hospital in Stockholm—”with 14 Nobel doctors, some of the smartest molly trotters on the planet”—benefiting from the most cutting-edge medical technology.

So did I hear that they’ve said to you that you could live until 120?

“One hundred ten. Yeah, 30 more years.”

Are they pretty confident you can get there?

“Oh yeah. Hell yeah. Nanotechnology, and the genome breakthrough at Cal State, that’s what the Nobel guys said is gonna allow it.”

Do you have any doubts?

“No, no, no. I feel like a child, man. I’m just starting.”

There almost seems no end to the projects he’s involved in: TV shows, movies, documentaries, branded products (headphones, luggage, sunglasses, pens), charities, hotels, tech initiatives, artist management. At one point, he asks for a laptop so that he can show me some of his young jazz protégés on YouTube, and spends about 20 minutes playing videos. “These motherfuckers are so talented. I just love seeing young people who got their shit together, man. They’re taking music back where it belongs. Because it’s not going anywhere right now. It’s champagne-selling noise.”

Do you like any of the people who are big right now?

“Yeah, I love Kendrick Lamar, I love Bruno Mars, I love Drake, I love Ludacris, I love Common. Mary J. Blige. Jennifer Hudson.”

But, say, Taylor Swift, I guess, is the biggest pop star on the planet in terms of sales right now and this week is about to sell over a million copies of her new album. Do you like her?

Jones makes a face, somewhere between disapproval and disdain.

What’s wrong with it?

“We need more songs, man. Fucking songs, not hooks.”

Some people consider her the great songwriter of our age.

He laughs. “Whatever crumbles your cookie.”

What’s missing?

“Knowing what you’re doing. You know what I mean? Since I was a little kid, I’ve always heard the people that don’t wanna do the work. It takes work, man. The only place you find success before work is the dictionary, and that’s alphabetical.”

So if you were producing a record for Taylor Swift, what would you have her do?

“I’ll figure something out. Man, the song is the shit—that’s what people don’t realize. A great song can make the worst singer in the world a star. A bad song can’t be saved by the three best singers in the world. I learned that 50 years ago.”

Plenty of people talk as though Taylor Swift has great songs.

“But they don’t know, man. They don’t know. I’ve come and gone through seven decades of this shit. Seen all that. Seen how that works. Ignorance is no thing.”

Swift is far from the first white pop star to underwhelm him. Here are some reflections on the early days of rock ‘n’ roll:

“I was with Tommy Dorsey when Presley showed up at 17 years old.… And Dorsey said, ‘Fuck him—I won’t play with him.’ He wouldn’t let his band play with him.”

Did you think Dorsey was right?

“Yeah! Yeah, motherfucker couldn’t sing.”

Did you understand why he was such a big deal?

“Yeah. Because it was the beginning. I recorded, did the arrangement, and produced Big Maybelle in 1955 with a little song called “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.” And four years later, Jerry Lee Lewis copies it (13), records it, and becomes a legend.

There are many ways in which Jones is perfectly plugged in to the here and now. In all kinds of ways. “We don’t have a cover, do we?” he asks at one point, then answers his own question. “No, they’re gonna want somebody younger. I don’t give a shit.” And from many of the allusions he makes, in many ways Jones clearly knows more about technology and where it’s heading than most people a third of his age. But as we get older, there are always some advances that pass us by. Sometime after Jones and I have finished watching his jazz prodigies, the Mac that has been set up in front of us goes to its default screen saver. It’s the one that has been available for over a decade, where the screen shows an ever-evolving swirl of lights, like a small rectangular window into the greatest aurora borealis ever seen. Catching this in the corner of his eye, Jones stops talking.

“What the fuck is that?” he says, taken aback.

And for a few moments, Quincy Jones seems completely, wondrously transfixed.

After Jones’s mother was taken away in a straitjacket, his father felt unable to look after Quincy and his brother, Lloyd. And so for a while they were shipped out of Chicago and lived with their grandmother in a shotgun shack in Louisville. (His grandmother had apparently once lived quite prosperously in South Charleston but sold all her property to send her children, including Quincy’s father, to Rutgers.)

“We used to eat rats, man. I’m telling you. I think back about that—that’s scary.” He sighs, as if to acknowledge how surreal the contrast is between the scene here, in his grand hilltop mansion surrounded by all his reminders of a lifetime of success and high living, and the world he is describing. “It’s life, man. When you’re 7 years old, you don’t give a fuck, you know. She’d send us down to the waterfront and tell us, ‘Just get the ones with their tails moving, because you know they’re alive.'”

“Just go down there and do it, man. Just get ’em. You’re 7—nothing’s scary to you, man. Get to a place where you see the access is close to the shore, and just grab them by the tail.”

And then you’d kill them?

“No, no, no, no, no, no, no. Take em, put ’em in the bag, and go home, and she takes care of that.”

How did she cook them?

“With some greens. Fry it, in a frying pan. Just like you do chicken, man. When you’re 7 you can’t tell the difference. Meat is meat. She’d put seasoning in with it. And red beans and rice.”

What did it taste like?

“Good, man. I mean, when you’re hungry. It’s an amazing journey, isn’t it?”

Quite a life, from eating rats there, to being here now.

“But your dreams always have to be big. And mine were huge.”

When you were younger, there were a lot of firsts: the first black man to do this, the first black man to do that.

“Yeah. Which means ‘only.’ “

Were you very conscious of that?

“Yeah. Of course.”

One example was when you started doing film soundtracks.

“Well, I wanted to do that since I was 15. But they didn’t use brothers. They only used three-syllable Eastern European composers—Bronislaw Kaper, Dimitri Tiomkin.”

And then in the first proper meeting you had in Hollywood, the producer walked in, saw you, and walked out again?

“Yes, he did. And he went back into the other room and said, ‘I didn’t know Quincy Jones was a Negro.’ Truman Capote, that motherfucker, he called [director] Richard Brooks up on In Cold Blood and said, ‘Richard, I don’t understand why you’ve got a Negro doing the music for a film with no people of color in it.’ And Richard Brooks said, ‘Fuck you, he’s doing the music.’ Richard was tough.”

When you heard that someone like Truman Capote had said something like that, what did you think?

“What is there to think, man? He’s racist like a motherfucker.”

Truman Capote eventually apologized, didn’t he?

“He sure did. After I get an Oscar nomination and he sees the film, he calls up: ‘Oh, Quincy, I’m so sorry’ and on and dun dun dun dun… That pisses me off, too.”

Is it true that he was crying?

“Yeah. Emotionally, it must have got to him. You know, that he made that kind of judgmental thing so quick. A person’s either like that or they’re not, man.”

It was shocking to me to learn that about him.

“You know, because it’s somebody you admire, and you see that they got this little old ragged-ass convention of racism going. But come on, man, ain’t nothing new. I’ve never turned my antennae off. I can’t.… You think racism is bad now, you should try the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s. Vegas in ’64 was fucked-up. That was why Frank had Mafia bodyguards for everybody in Basie’s band and me. Lena, Belafonte, Fats Domino, they used to play the main theater for $17,000 a week, used to have to eat in the kitchen. Couldn’t go in the casino. Had to go to a black hotel across town. In ’64! You can’t even imagine that. But if you’re black, that’s what you get used to in America.”

And when you were in the middle of that craziness, what were you thinking? Are you angry, or just baffled?

“Well, listen, anger doesn’t get anything done, so you have to find out: How do you make it work? That’s why I was always maniacal about transforming every problem into a puzzle which I can solve. I can solve a puzzle—a problem just stresses me out.”

Jones’s first proper, sustained job as a professional musician came when he went on the road, playing trumpet with the band leader Lionel Hampton, when Jones was 18. Hampton first invited Jones to join his touring band when Jones was 15, and Jones had even gotten on the bus, ready to leave, but Hampton’s wife and business manager threw him off because he was too young. At 18, he was ready—or as ready as one could be: “The band bus with Lionel Hampton got 33 people on it. The front half of the right side, we call them the holy rollers. The weed smokers behind them, that’s us. The boozers here and the junkies there. Every time we’d go to Detroit, at the Majestic hotel, standing in front, with his Italian shit on and amber glasses: Malcolm X. Detroit Red. That’s where we bought our dope. It was before he went to prison.”

“Yeah! He was the dope dealer. That’s how he went to prison.”

So you would personally buy drugs off Malcolm X?

“Personally?” He nods. “Shit, everybody in the band bought it! The junkies used to call cocaine ‘girl’ and heroin ‘boy.’ That’s because they said cocaine would take you from your woman.”

So why was heroin ‘boy’?

“Because it’s masculine. It’s a strong drug. And it won’t bother you as long as you give it everything it wants. But it wants more and more all the time.”

Did you try everything over the years?

“I’ve tried everything. Amyl nitrate. Methedrine. Benzedrine. Everything. Ray had me on heroin for five months.”

How old were you then?

“Fifteen.”

Did it get bad for you?

“Yeah, I started shooting. And then I fell down five flights of stairs, and I said, ‘That ain’t gonna work.’ And it’s the best thing that ever happened to me, because when I was in New York, I was hanging out with Howard McGhee and Earl Coleman and Charlie Parker and shit—I would have been a junkie for life.”

Was it easy to stop?

“I fell down five flights of stairs, brother. I didn’t need any more inspiration than that. Shit, it’s the last time I did it. Because I can stop like a motherfucker. Anything. Cigarettes. Alcohol. I just stop, man.”

Obviously, Ray Charles carried on for a long time.

“Oh, please—he went 30 years with heroin, and then the police told him he couldn’t get his license to play clubs unless he stops. And he did, and the 32 clubs gave him the licenses back. And then he started on black coffee and Dutch Bols gin for 25 years.” (14)

When he was still using, would you talk to him about it?

“No, I wouldn’t talk. Talk about what? I’ve seen him shooting in his testicles, man. Because heroin’s a strange drug. Ray, all of his veins were dried up and black, and he’s shooting himself in the testicles, man.”

And you’d see that?

“Yeah, he had a guy do it. It was horrible.”

The second time Quincy Jones sidestepped fate came in 1974, when he was 41. One day he felt a pain in his head, and then he collapsed. A brain aneurysm.

“It was scary,” he says. “Like somebody blew my brains out. The main artery to your brain explodes, you know.”

He had brain surgery, after which he was told that he had a second aneurysm ready to blow. And so, once he was strong enough, he had a second operation. Later he was told that he’d had a one-in-a-hundred chance of surviving.

By this point, Jones was already very successful—as an arranger, as a solo artist, as a composer for movies and TV—but he’d first made his name as a trumpet player. Now he was told that he had a clip on a blood vessel in his brain, and that if he blew a trumpet in the ways that a trumpet player must, the clip would come free and he would die. He could never play the trumpet again. And so he never has.

That’s how this story is usually told, anyway. But it’s not quite true. Jones was indeed given that advice, but shortly after he recovered he went on tour in Japan. And he took his trumpet with him. One day, as he blew, he felt a new pain in his head, and he was subsequently told that the clip had nearly come loose. “I couldn’t get away with it, man,” he concedes. This time he listened.

Isn’t it crazy that you even tried?

“Yeah. Yeah. Well, I missed the trumpet.”

His collection of trumpets, including Dizzy Gillespie’s, is mounted on the wall of his living room, behind the bar, and he describes the instruments with evident love.

Does any part of you still miss it?

“Very much, man. Very much. I finger all the time. But I can’t touch it.”

There’s something very beautiful and haunting about this that stays with me: the trumpet player fingering notes on an invisible trumpet that he knows he can never dare hear.

You wrote in your book that you’d heard your father had a white father who’d killed someone, but you weren’t sure of the story.

“Yeah, Welsh. I had to find out later through Alex Haley. (15) [My grandmother] was an ex-slave, you know. And her first husband was black. And then, I’m sure it was not planned, one of the slave owners was a Welshman. They had three girls and my father, and they were light-skinned, high yellow, straight hair.”

But when your father was alive, you never asked him about his father?

“No.”

How come?

“Because, you know, I don’t know…it’s etiquette.”

So he never said, “My father was white”?

“Nope. Nope. Back then, they were ashamed of it, man. So I would never press that. Because it wasn’t by consent, you know. They raped a black woman.”

You assume he was the product of a rape?

“Yeah. That happened all the time. That’s the story of America.”

So he never knew his father?

“No. It’s heavy. My people were from Mississippi. Oprah and I kid all the time—we call each other ‘two motherless motherfuckers from Mississippi.'”

But your grandmother had several children with the same man, so whatever happened continued for a sustained period of time?

“Yeah. That’s the way it was back then. They did whatever they wanted to do. They’re the owners.”

A conversation about Charlie Parker, Tupac, Michael Jackson, and Prince:

When people think about Quincy Jones, what do you think they misunderstand about you?

“Oh, that I only like blondes. How stupid can that be, when you’re in South Africa and Cairo and Brazil and China—looking for a fucking blonde?”

I didn’t know that was a perception of you.

“Well, because I had three wives, white wives, and they stereotype, you know. But they wrong like a motherfucker, man. You ever see Black Orpheus? That was my old lady, Marpessa Dawn. Gorgeous lady, man.”

You did get some criticism for having white wives, didn’t you?

“I don’t give a fuck. Because they think that’s all you like, but that’s stupid, man. Here’s what you’ve got to understand: The interracial thing was part of a revolution, too, because back in the ’40s and stuff, they would say, ‘You can’t mess with a white man’s money.… Don’t mess with his women.’ We weren’t going to take that shit. Charlie Parker, everybody there, was married to a white wife.”

And it felt like there was some sense of liberation in that?

“Yeah! It was freedom, man. Do what you want to do, and nobody can tell you what to do. Charlie…I used to go to things with Charlie Parker, man—boy, he’d have everybody smoke some weed and he’d have, like, the founders of Sears Roebuck, the ladies walking around the pool, all of them nude, man. Him playing alto, buck dancing around the pool. Them cats didn’t play.”

One of his most famous critics was the newly famous Tupac Shakur, who said in a 1993 interview with The Source, “Quincy Jones is disgusting. All he does is stick his dick in white bitches and make fucked-up kids.”

That was a terrible thing that Tupac said about you.

“Yeah. And my daughter kicked his ass, boy. Rashida, she was in Harvard then: ‘Motherfucker, you wouldn’t be where you are if they hadn’t done what they did.'” (16)

Still, it was an awful thing to say.

“I know, but people, you know. The haters everywhere. You know, we became good friends after that. We came almost in love with each other. I was going to do a film with him and Snoop Dogg, Pimp, [about] Iceberg Slim.”

You met him at a deli, right?

“That’s when he first met Kidada. (17) He was hitting on her—he changed his mind now, you know? And I went over the back of the seat and did like that on his shoulders: ‘Pac!’ ” Jones acts out grabbing hold of Tupac from behind. “And then I said, ‘Come here, motherfucker, I’ve got to talk to you.’ And we went and talked, and after that we hugged and made up.”

Did he apologize straightaway?

“Yes, he did. Yeah. He said, ‘I’m sorry I said it.’ “

Did he explain why he said it?

“No, it wasn’t that kind of relationship. Just trying to be a rapper, man. Like the swagger that’s part of their game, you know. I know those motherfuckers backwards.”

How could you forgive someone who could say that?

“I forgive everybody. Forgiveness is what it’s all about. Forgive us our trespasses and forgive those who trespass against us. It’s imperative. It was no problems after that. And I know his mother, Afeni, who was a pain in the ass. She’s dead now. They want us to take over the estate now, my son and I. Three or four estates they want us to take over. In fact the Jacksons are coming to us now, even after the court thing we had. (18) Jermaine was here last week with his 21-year-old son, and I want to do a Broadway show with him on Michael. Julie Taymor to direct—that’s my baby, biggest in history, Lion King. And use Jermaine’s son, who sings and dances just like Michael.”

You first met Michael when he was 12, right?

“Yeah. Aretha, 12. Michael and Stevie [too]. That’s heavy, isn’t it? It means if you’ve got it at 12, you know you’re going all the way.”

What do you think Michael’s greatness was?

“He had a perspective on details that was unmatched. His idols are Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, James Brown, all of that. And he paid attention, and that’s what you’re supposed to do. That’s the only way you can be great, you know, is pay attention to the best guys who ever did it. Amazing process of producing those albums, man. You know at Motown they sing high all the time, and I had to send him to Seth Riggs (19) to give me another fourth range on top and a fourth on bottom because I need a little more range. I said, ‘Michael, I need you to just murmur and beg, and [use] soft falsetto voice low, so you get a contrast to the dee do da da day do do. I needed him to beg, and I went through the whole nine yards. It’s like a film director, man. But, you know, here’s the bottom line: If the cover’s fucked-up, if it’s the wrong studio, wrong engineer, wrong background groups, wrong tempos for the songs, and all that stuff—if that’s fucked-up, it’s all the producer’s fault. If it’s a hit, the artist wants credit for everything. That ain’t never gonna change. Prince, all of them. Please—I worked with everybody in the fucking world in music.”

Prince appeared in the studio, right, back when you and Michael were recording ‘Off the Wall’?

“Yeah, he showed up in the back of a car with a brother who was managing him, and he was like a deer in the headlights. He didn’t have a top on. Did you ever see that thing with James Brown?”

Oh yeah.

Jones is referring to the legendary evening—August 20, 1983—when both Michael Jackson and Prince attended a James Brown show at the Beverly Theater in Los Angeles.

“That’s heavy. He made a damn fool out of himself, didn’t he?” says Jones, and the star he is referring to is Prince. Jackson had film of what happened that night. “Prince told Michael he’d kill him if he showed it to anybody,” Jones explains, but one way or another, time-coded raw footage of what took place that night eventually surfaced. First Brown invites Jackson to the stage. Jackson sings a few phrases, spins, moonwalks, then embraces Brown and can be seen whispering to him. Brown then calls for Prince. After a delay, Prince gets onstage, takes a guitar, jams a little, then strips off his shirt. He does some mic-stand tomfoolery, dances a little more, then nearly tumbles into the audience trying to pull down an oversize streetlamp prop. It was a superstar face-off that has often been seen as a triumph for Michael Jackson, and a rare humiliation for Prince.

He spoke to Michael after the show?

“Oh yeah, he spoke to him. He waited in the limousine to try and run over him and La Toya and his mother.”

How do you know Prince was trying to run him over?

“He knew. Michael knows shit. He was there. He said that was his intention.”

Michael told you that?

“Yeah.”

What did he think of what Prince had done onstage that night?

“It was just very obvious what the hell happened—made a damn fool out of himself. Michael went up there, in 40 seconds, sang I love you I love you. Then they went up-tempo and he did a little dance and did the moonwalk and whispered in [James Brown’s] ear, ‘Call Prince up—I dare him to follow me.’ “

A further landmark in their uneasy rivalry came when Jones suggested to Jackson that Prince duet with him on the title track of his Bad album. “So we invited [Prince] over to Michael’s house at Hayvenhurst. He came in and he had an overcoat on, and he had a big white box labeled camille. He called Michael ‘Camille.’ ” Prince, it seems, had brought a gift for his host. “The box had all kinds of stuff—some cuff links with Tootsie Rolls on them. Michael was scared to death—he thought there was some voodoo in there. I wanted to take it, because I knew Michael was gonna throw it away.”

What happened to it?

“He threw it away. In the garbage.”

How did the conversation about doing the song together go?

“Well, we sat at a table that held 24 people, at his house, family table, I said, ‘Michael…Smelly, (20) you sit over there so he doesn’t feel like we’re ganging up on him.’ It started off funny. Michael said, ‘I never been to Minnenapolis.’ [Prince] said”—snapping angrily—” ‘It’s Minneapolis!‘ Oh God…man, this is not going too well. Then Janet went by. [Prince] said, ‘Relax your lips, girl.’ And it was not going well, that’s for sure. Then we went upstairs, and he saw the chimpanzee and the snake, he said, ‘Now, that’s interesting.’ And then he says to me, ‘He doesn’t need me on this—it’s going to be a hit anyway.’ Which is true.”

You were around in the era when the animals started appearing, weren’t you?

“Yeah. Muscles”—Jackson’s boa constrictor—”and Bubbles.” The chimp. “Muscles used to come and wrap around me, my leg, around the chair, and crawl across the console. That was a big motherfucker, man.”

What did you think?

“Oh, it scared me to death, man. I ain’t gonna lie. And the chimpanzee, whatever the fuck it was, he was a pain in the ass. He bit Rashida. My poor baby.”

If that was my daughter, I’d be kind of angry.

“Yeah, I was angry.”

What did you say?

“Well, what do you say? Shit. After it’s already happened, what the fuck can you do? I remember one day we were out there working at Hayvenhurst, and we couldn’t find Muscles, and we went downstairs—they were refurbishing this room down there—and here this cat, man, is hanging out of the parrot cage. His mouth is inside, but he just ate the parrot so he couldn’t get out of the cage. So he’s just hanging there till he digests it.”

This is Michael’s parrot he’s eaten?

“Michael’s parrot. The snake didn’t want to hear that shit.”

Would you ever say to Michael, “This stuff is strange”?

“No, man, you don’t do that. Come on. I don’t get into that kind of judgment. I really don’t. I just think that’s who they are, you know. Just see what you can put up with, what you can’t.”

It sometimes seems as though it would be easier to go through the history of the past 70 years and try to isolate the most significant figures Quincy Jones never encountered.

We’ll be talking, and suddenly he mentions that on the other side of the room there are cards from Picasso’s wife, Jacqueline.

“With her notes on them in French. Because they used to live next door to us in Cannes in 1957. Jacqueline and Picasso. We had lunch with him. He was a character, man. He was fucked-up with absinthe all the time. We both ordered sole meunière, which is one of my favorite dishes of all time from Paris, and after he’d finish he’d take the bones and push it out in the sun and let the sun parch the bones, and he’d take out these three colors, orange and blue and red, and when the waiter would say, ‘L’addition, s’il vous plaît,’ Picasso would push that. And you look all across the walls, his bones with his writing on them. That’s how he paid his bills. He was a bad motherfucker, man.”

What would you talk about?

“I was afraid to talk to him, really. Because that’s a big motherfucker, man.”

And then Jones started telling me what it was like to discuss music with Stravinsky.…

I don’t need to, but every now and then I bring up a name myself:

You were also close with Marlon Brando?

“Oh man, like my brother. I came out of Birdland (21) when I was 18 years old – Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, and Marlon. He had a red fedora on, had just smoked a joint. He’d just done A Streetcar Named Desire, and he was going up to Harlem that night. He didn’t say to the brothers, ‘Go with him.’ He said ‘I’m goin’.’ He didn’t ask us to do shit. And he went up there—he was the only white dude in the whole place. So he went in the joint, all black, and he saw a booth over there with a guy with a hat on and five girls. He didn’t realize the guy was a pimp. And he went over, put his charm on ’em, and said, ‘I’d like to dance,’ took her out on the floor for about 30 minutes. He’d dance his ass off. And went back:, ‘Thank you very much.’ Got that charming smile. And then Marlon looked back over and the guy was staring at him, right? He’d smoked a joint so he got paranoid, you know, so he went back over to the guy and said, ‘Look, I was a gentleman, man, I came and asked you first, man, right?’ And the guy was not looking at his face. He had a toothpick and was looking at his belt buckle. Said: ‘The name ain’t “man,” it’s “Leroy.” L-E-R-O-motherfucking-Y.’ At that, Marlon turned around and freaked out. He got paranoid—got outside and ran 15 blocks, nobody after him. So we called each other Leroy till the day he died.”

Why did the two of you bond?

“I don’t know, man, but it was strong. (22) Number one, we lived right next door to each other.”

Didn’t you plan to act in a movie together?

“Yes! What was the name of that?”

Was it called ‘Jericho’?

“Yeah! How’d you know? I still got the script. We were two CIA guys. It was funny, man. I met him in 51—it was about 20 years later. He was a wild dude, man.”

What would you and Marlon do when you got together?

“Everything. Party our ass off. We’d go over to Maverick Flats in the ghetto. (23) His son Miko, I took him to San Diego with us to get the first platinum record on Thriller, and he met Michael, and Michael’s family hired him to be part of their team. He’s still with them. Marlon always figured he had to pay. I said, ‘Motherfucker, you don’t have to pay me back.’ So he said, ‘Oh, get [your son] some dance lessons.’ I said, ‘Leroy, he’s a star breakdancer at 14 years old in Sweden, man. He don’t need no dance lessons.’ He said, ‘Okay, I’ll get him acting lessons.’ So we go over there and he’s got a kimono on and a ponytail. I got a tape on that.” (24)

How were the acting lessons?

“The funniest thing you ever saw in your life. He said, ‘Knowledge on acting is very important for television and movies, but it’s ten times more important when you’ve been out with one woman all night till 5:30 in the morning and you have to go home to your wife. And that’s what makes it important.’ Snoopy (25) looking at him like he’s crazy. He’s 17 years old—he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. So [Marlon] says, ‘You go on around the back of the house, turn the motor off on the car, and let it slide down the hill. You get out, you take off your shoes’—Snoopy is looking at him like he’s insane— ‘and start to sneak up the back steps. And you get halfway up, and your wife’s sitting there, 5:30 in the morning, with her hands on her hips, giving you a cold hard stare. You get one take.’ There’s silence on the tape for a while. He says, ‘Goddamn, I’m glad to see you—I broke my foot.’ ‘Unbelievable, man. You gotta make up a story she’s gonna believe at 5:30 in the morning. She knows you’ve been out fucking around!'”

Let me ask you about someone completely different. You really met Leni Riefenstahl? (26)

“Yes! I wouldn’t make it up. I’ve been a fan of hers since Triumph of the Will. I mean, that woman was one of the greatest filmmakers that ever lived.”

How did you come to meet her?

“She knew I was a fan, and I was over there [in Berlin]. Nastassja was doing a film with Wim Wenders. Came to the hotel one day and there was an invitation—she wanted me to have lunch with her. And that’s the most incredible meeting I’ve ever had in my life. Because I knew all about her. She was Goebbels’s girlfriend—he was like the publicist for the Third Reich, you know. She looked like Hedy Lamarr when she was young. She said she used 211 cameras. I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘We were doing a recruitment film for Hitler—think I’m going to tell Hitler, “One more time, Adolf!”?’ And then she told me something that really hit home. She told me everybody in the Third Reich was on cocaine. See, I worked for pimps when I was 11, and they used to do that, too—they’d take cocaine because it raised the propensity for violence, from the primate brain. That’s the primate in us, the four F’s: Fright, Fight, Flight, and Fuck. I never understood why sex and violence were so commercial—it’s the primate brain, the animal brain. Heavy.”

She saw Hitler using cocaine?

“Of course, man! She was Goebbels’s girlfriend.” (27)

So how does she think it affected Hitler?

“Well, shit, the history proves how it affected him. He killed every motherfucker he could see.”

You think a huge part of the horror of Nazism was just down to cocaine?

“I think it had a lot to do with it. When she said that, it opened up a door for me. Because I’ve been around that shit all my life.”

Some people would be judgmental about having lunch with someone who was so closely involved with the Nazi Party.

“Oh, give me a fucking break, man, please. This is a human being, man. And a very special human being. It was never political. It was about her passion for her profession.”

Still, I wonder if she regretted being in all of that.

“No, because she never got involved—she never got passionate about what the Third Reich was doing. She wasn’t into it. I could tell. You have to read between the lines, too.”

Jones and Ray Charles rehearsing for a televised tribute to Duke Ellington, 1973.

(Photo by David Redfern/Redferns)

A third time Quincy Jones’s life might have come to a premature halt:

Barely a few hundred yards away from where we sit tonight, on a nearby hillside, is a house with a troubled history. In the late 1960s, Jones nearly bought the house, but the owner at the time said he would only rent it, so Jones bought a house from the actress Janet Leigh on Deep Canyon Drive instead. Some people he knew moved into the other house.

In early 1969, Steve McQueen called Jones and asked him to go and see a rough cut of Bullitt. Jones brought along his hairdresser, a man named Jay Sebring, and after the movie, they made plans for later that evening.

“He said, ‘I’ll meet you at Sharon’s, because I’ve got some stuff for your hair,’ ” Jones remembers. “I was losing my hair.”

But Jones didn’t go. “I forgot about it,” he says.

The next morning his friend Bill Cosby (28) called from London.

“He said, ‘Man, did you hear about Jay?’ Because we all used to hang out together. He said, ‘Did you see that he’s dead?’ I said, ‘Impossible, man, I was with him last night.’ “

At the dinner party Jones had missed, at Sharon Tate’s house, all five guests had been brutally murdered. (29)

What did you think when you realized how close you’d been?

“Oh my God, it was freaky. Because they hung him up, man, and cut his nuts off and everything—Jay Sebring. And they cut her belly open with the baby, you know.” (30)

When something like that happens—nearly being at this terrible event—what does it make you think?

“Man, it’s been happening to me all my life. It’s just unbelievable, man. You feel blessed that somehow you forgot, or whatever. Jesus Christ. Ain’t never forget that. That’s the Ghetto Gump shit. Life is a trip, man. Life is a trip.”

After I leave—it’s shortly before midnight—Quincy Jones will do some Sudoku.

“Keeps dementia and Parkinson’s away,” he says. “I’m fighting that like a warrior. Got to challenge the brain. Use it or lose it.”

And, all his life, Jones has relished that moment around midnight when something new begins. “The muses come out at midnight,” he says. “No e-mails, no faxes, no calls.” And when the rest of the city is fully asleep, that’s when Quincy Jones, three months short of his 85th birthday, will really get to work.

“I’ll write music,” he says. “I’m writing a street opera—for my album.”

Finally, at around ten in the morning, Jones will allow himself to rest.

“Life’s an amazing journey, isn’t it, man?” he says. “Every day I think about it. It’s just something else. I love every step. I appreciate all of it. Every drop.…”

He talks again about all the birthday tributes in the works: the biopic, the Netflix doc, the TV special.

“Fucking insane,” he says. “They be thinking I’m 84 and retired and all that shit. They wrong, man. Oh baby! I am never retiring!”