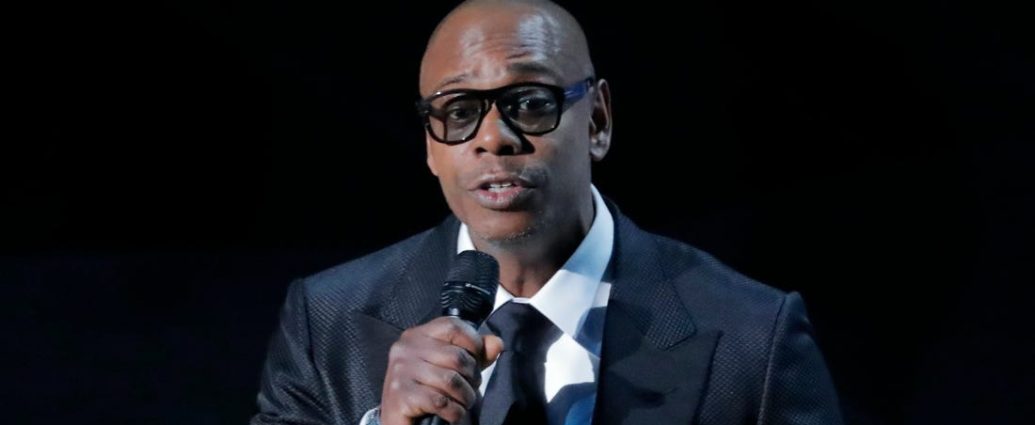

Dave Chappelle’s Netflix Special: Three Key References to Know

As he addresses police brutality, the death of George Floyd and nationwide protests in “8:46,” the comic examines overlooked subjects.

-

Dave Chappelle released a lacerating new special, “8:46” — the length of time that a police officer held his knee on George Floyd’s neck as Floyd pleaded for his life — that has become among the first live shows in the Covid era to reckon with the protests gripping the nation.

-

“This is weird,” Chappelle tells audience members, wearing masks in socially distanced seats.

The show was taped in Ohio on June 6, and a title card explains that it was Chappelle’s first performance in nearly three months. Dressed in black, he refers regularly to a notebook and smokes a cigarette onstage.

Chappelle’s performance isn’t much of a comedy set, because, as he notes, there aren’t really any jokes. Instead, it’s a raw accounting of police brutality, punctuated with images of black men who died at the hands of officers, and deftly interweaving his own personal history.

He covers a wide range of topics, including the media, the death of Kobe Bryant, and his family members, some of whom were in the audience. But three subjects, including a run-in Chappelle had with an Ohio police officer who went on to kill a young black man, are not well known. Here’s more context for the special.

The Killing of John Crawford III

In 2014, days before the police killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., a 22-year-old black man named John Crawford III was shot and killed in a Walmart in Beavercreek, Ohio — Chappelle’s community — by a white police officer. The night before, Chappelle says in the special, the same officer pulled him over. He “let me off with a warning and the next day kills a kid.”

Walmart’s security footage, as described in a report in The Guardian, showed Crawford walking around with a BB gun that was for sale in the store, available without a box. Another shopper called 911, reporting a black man waving around a weapon. The footage did not show Crawford waving anything, according to The Guardian. He was talking on his cellphone to his girlfriend when the police shot him, the footage shows.

- Thanks for reading The Times.

A grand jury declined to indict the officer or his partner. The Justice Department investigated, but no charges were filed.

By 2019, the city of Beavercreek had spent nearly $600,000 on legal fees, according to the Dayton Daily News. And in May, the city agreed to a $1.7 million settlement with Crawford’s family. The officer who shot him, Sean Williams, returned to active duty in 2017. He was reassigned as a detective, the Dayton Daily News reported.

The Case of Christopher Dorner

Chappelle and other comedians were referenced in the manifesto of Christopher Dorner, a former Los Angeles police officer who shot and killed four people, including colleagues, in 2013, before committing suicide as authorities closed in on him. In Chappelle’s telling, Dorner, who also served in the Navy Reserves, was pushed out of the police department though he tried to do everything right, including pursuing legal avenues to appeal his dismissal.

Chappelle connects Dorner, who was black, to another black former military man who killed five white police officers in Dallas in 2016. In the military, the comedian says, these men were trained “to fight acts of terror.” That, he suggests, is what the police represented.

His Illustrious Great-Grandfather

Most personally, Chappelle brings up his great-grandfather, William D. Chappelle, who was an A.M.E. Church bishop in South Carolina and president of Allen University, a historically black school that is now home to a landmarked building named for him.

In his seminal 2016 appearance on “Saturday Night Live,” just days after the election of Donald Trump, Chappelle closed his monologue by talking about how few black people had been welcomed to the White House throughout history. “To my knowledge, the first black person that was officially invited to the White House was Frederick Douglass,” he said. “They stopped him at the gates; Abraham Lincoln had to walk out himself and escort Frederick Douglass into the White House. And it didn’t happen again, as far as I know, until Roosevelt was president.”

He had made a mistake, he said in the special. There was another person who made it to the White House in those years: his great-grandfather, who led a delegation there in March 1918, protesting violence against black people during the Great Migration, including, Chappelle said, the lynching of a South Carolina man over a fee at a grain elevator.

The life and morality of the bishop, who died in 1925, seems to have new resonance for Chappelle, who first visited his namesake building at Allen University three years ago and gave a speech.

He said there, “This idea that what you do in your lifetime informs the generations that come after you is something I keep thinking about.”

“My great-grandfather built something more substantial than buildings, he built a community, and more importantly than a community, he built a way,” he continued.

Then Chappelle, in an uncharacteristic suit and tie, seems to notice someone over his shoulder. “Hello, police,” he said. “He’s standing over there, like, ‘So this is what black people talk about.’”

The audience laughs, and Chappelle goes back to his speech, a call for the ethical clarity that helped his family build its legacy.

His great-grandfather was born a slave, Chappelle says in the special, and crusaded then as people in the streets do now. “These things are not old, this is not a long time ago,” he says. “It’s today.”