Did Man Who Armed Black Panthers Lead Two Lives?

In the mid-1960s, the Black Panthers came to symbolize black militant power. They rejected the nonviolence of earlier civil rights campaigners and promoted a radical socialist agenda.

Styled in uniforms of black leather jackets, dark sunglasses and black berets, the Panthers were never shy about brandishing guns, a sign that they were ready for a fight.

The images and message terrified J. Edgar Hoover, then the director of the FBI, who called the group “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” Hoover launched a covert campaign to undermine the Panthers.

Since the release of more FBI records from the time, a new question has come to the fore: Did the man who armed the Panthers work for the FBI?

Founded in 1966, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense insisted that someone had to stand up to the police.

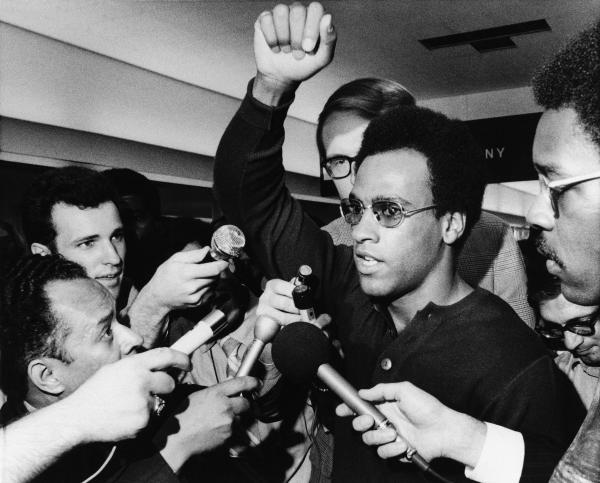

Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale called for “an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people.”

“This is very, very important, and here’s — whether you know it or not — is where you start dealing with the black revolution,” he said.

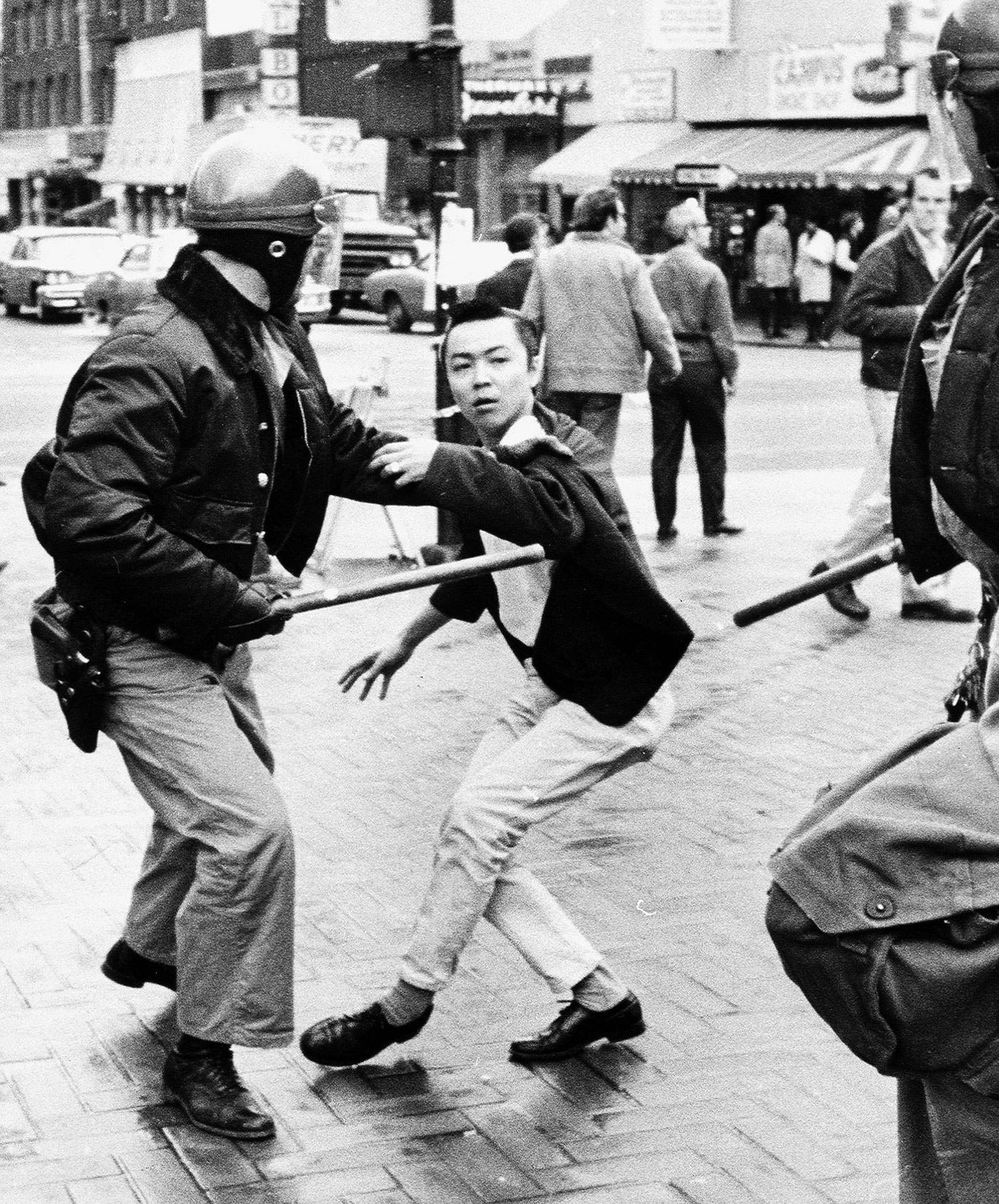

The Black Panthers armed themselves for community patrols. The idea was to police the police force, which was largely white and often brutal. It was a time of high emotion, and as the Panthers grew in membership and influence, it eventually led to gunbattles leaving dead police and dead Panthers.

A couple of years later, Seale published a memoir revealing that some of the very first guns the Panthers got their hands on came from, in his words, “a Japanese radical cat,” a man named Richard Aoki.

Aoki was born in the San Francisco Bay Area and was interned along with tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans during World War II. After the war he grew up in predominantly black West Oakland. Aoki joined the Army straight out of high school, serving one year of active duty and seven years in the reserves.

In a 2009 documentary about the Black Panthers produced by the Peralta Community College District in Oakland, he described himself as a gung-ho soldier.

“I wanted to be a career soldier,” Aoki said. “I wanted to be the very first Japanese-American general in the United States Army and work my way up through the ranks.”

That dream had faded by the time he was honorably discharged in 1964, after he became disenchanted with the war in Vietnam. He gravitated toward left-wing groups and attended Merritt College in Oakland. That’s where he met the two students who were creating the Black Panther Party, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton. He says Newton asked him to join the party.

“And I said, ‘Say what? I know you two are crazy, but are you colorblind? You know I’m not black,’ ” Aoki says in the documentary. “He said, ‘I know you’re not black, Richard, but I’m asking you to join because the struggle for freedom, justice and equality transcends racial and ethnic barriers.’ “

Aoki became the minister of education for the Black Panther’s Berkeley branch. Three years later, he was a prominent leader of a sometimes violent student strike demanding ethnic studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

All the while, no one suspected the makings of a mystery that lasts until today: Was Black Panther leader Richard Aoki living two lives?

“Richard Aoki is a fascinating person,” says Seth Rosenfeld, the author of Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals and Reagan’s Rise to Power, which chronicles covert surveillance of student protesters at UC Berkeley. “On the one hand he was Japanese; on the other hand he was American. On the one hand he was a gangster; on the other hand he was a brilliant student. On the one hand he was a militant activist; on the other hand he was working for J. Edgar Hoover.”

Rosenfeld bases that claim on documents released by the FBI under the Freedom of Information Act and reporting he did for the book. He has successfully sued the FBI five times to get access to more than 300,000 pages of heavily redacted documents. More than 200 pages relate to Aoki’s activities as a paid informant from 1961 to 1977.

Rosenfeld spent 30 years researching his book. He says he first heard that Aoki was an FBI informant in 2001 from a now deceased former agent named Burney Threadgill.

In 2007, Rosenfeld got a chance to ask Aoki about those claims in an interview, which he shared with NPR.

In the taped interview, Aoki is not definitive about his relationship with the FBI. Asked if he knows Threadgill, Aoki says, “No, I don’t think so.”

When Rosenfeld tells him Threadgill said he worked for the FBI, Aoki says, “Oh, that’s interesting.”

After Rosenfeld presses him about whether he worked for the FBI or was paid by the FBI, Aoki says, “I would say [it’s untrue].”

But when Rosenfeld says he is trying to understand the complexities of the situation, Aoki says, “It is complex. I believe it is. Layer upon layer.”

Exactly how to read Aoki’s responses in the interview is up for debate. For those who reject Rosenfeld’s conclusion that Aoki did indeed work for the FBI, the evidence isn’t compelling, and there are a lot of people who don’t believe it.

Diane Fujino, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who published her own biography of Aoki this year, has been Seth Rosenfeld’s most outspoken critic. Fujino says she has seen the FBI documents but still has doubts.

“I’m not a conspiracy theorist. I’m not going and saying this was all fabricated. I do question the timing of some of these things,” Fujino says. “For an FBI agent to reveal the identity of an informant is a serious breach of FBI protocol. You know, why would he do this all of a sudden? It seemed a little odd.”

An FBI spokesman declined to comment on Rosenfeld’s allegations.

Rosenfeld says more FBI records probably would answer some important questions about its relationship with Aoki.

“What did the FBI know about Richard Aoki arming the Black Panthers, and was the FBI involved?” Rosenfeld says. “I don’t know the answer to that question, but I think it’s incumbent on the FBI to offer a full explanation to the community, especially in light of the fatal consequences of the Panthers’ involvement with guns.”

Aoki took his secrets to his grave. He was 71 and ill when he committed suicide in 2009.

But before shooting himself, Aoki neatly laid out two sets of clothing: his freshly pressed Army uniform, and a black leather jacket, black trousers and beret — his uniform as a Black Panther.

9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))

AUDIE CORNISH, HOST:

From NPR News, this is ALL THINGS CONSIDERED. I’m Audie Cornish. J. Edgar Hoover famously called the Black Panthers, without question, the greatest threat to the internal security of the country. Well recently, released documents appear to show that Hoover had an informant inside the group. That man committed suicide a few years ago. But NPR’s Richard Gonzales reports, he was a fascinating character who stoked questions about his allegiances to the very end.

RICHARD GONZALES, BYLINE: Their official name was the Black Panther Party of Self Defense.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED AUDIO)

GONZALES: Founded in 1966, the group insisted that someone had to stand up to the police.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED AUDIO)

GONZALES: Black Panther co-founder, Bobby Seale:

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED AUDIO)

GONZALES: It was a time of high emotion as the Black Panthers armed themselves for community patrols. That eventually led to gun battles leaving dead police and dead Panthers. A couple of years later, Seale published a memoir revealing that some of the very first guns the Panthers got their hands on came from, in his words, a Japanese radical cat. His name was Richard Aoki.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED AUDIO)

GONZALES: Aoki was born in the San Francisco Bay Area and was interned along with tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans during World War II. After the war, he grew up in predominantly black West Oakland. Aoki joined the Army straight out of high school, serving one year of active duty and seven years in the Reserves. In a 2009 documentary about the Black Panthers, produced by the Peralta Community College District, Aoki described himself as a very gung-ho soldier.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED AUDIO)

GONZALES: But that dream had faded by the time he was honorably discharged in 1964 after he became disenchanted with the war in Vietnam. He gravitated towards left wing groups and attended Merritt College in Oakland. That’s where he met two students who were creating the Black Panther Party: Bobby Seale and Huey Newton.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED AUDIO)

GONZALES: Aoki became the minister of education for the Black Panther’s Berkeley branch. Three years later, he was a prominent leader of a sometimes violent student strike, demanding ethnic studies at UC Berkeley. All the while, no one suspected the makings of a mystery that lasts until today. Was Black Panther leader, Richard Aoki, living two lives?

SETH ROSENFELD: Richard Aoki is a fascinating person.

GONZALES: Seth Rosenfeld is the author of a new book about the FBI’s covert surveillance of student protesters at UC Berkeley in the 1960s.

ROSENFELD: On the one hand he was Japanese, on the other hand he was American. On the one hand he was a gangster, on the other hand he was a brilliant student. On the one hand he was a militant activist, on the other hand he was working for J. Edgar Hoover.

GONZALES: Rosenfeld bases that claim on documents released by the FBI under the Freedom of Information Act. He has successfully sued the FBI five times to get access to more than 300,000 pages of heavily redacted bureau documents. You can see some of those documents at npr.org. More than 200 pages relate to Aoki’s activities as a paid informant from 1961 to 1977. Rosenfeld spent 30 years researching his book. He says he first heard that Aoki was an FBI informant in 2001 from a now deceased former agent named Bernie Threadgill. In 2007, Rosenfeld got a chance to ask Aoki himself about those claims. And he shared his tape recordings of that interview.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED AUDIO]6)

GONZALES: Rosenfeld kept pressing Aoki.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED AUDIO)

GONZALES: Huh? What is Aoki saying here? Is he confessing or simply being coy? The answer may depend on whether you accept Rosenfeld’s conclusion that Aoki did indeed work for the FBI. There are a lot of people who don’t believe it. On a recent weekday night, a few dozen people, many of them old activists, Panther supporters or family and friends of Richard Aoki, met in an Oakland library to discuss Rosenfeld’s allegations.

DIANE FUJINO: I’m not a conspiracy theorist. I’m not going and saying this was all fabricated. I do question the timing of some of these things.

GONZALES: Diane Fujino is a professor at UC Santa Barbara and author of her own biography of Richard Aoki published this year. She has been Seth Rosenfeld’s most outspoken critic. Fujino says she’s also seen the FBI documents but she still has her doubts.

FUJINO: For an FBI agent to reveal the identity of an informant is a serious breach of FBI protocol. You know, why would he do this all of a sudden? It seemed a little odd.

GONZALES: An FBI spokesman declined comment on Rosenfeld’s allegations. Rosenfeld says more FBI records probably would answer some important questions about its relationship with Richard Aoki.

ROSENFELD: What did the FBI know about Richard Aoki arming the Black Panthers and was he FBI involved? I don’t know the answer to that question. But I think it’s incumbent on the FBI to offer a full explanation to the community. Especially in light of the fatal consequences of the Panthers’ involvement with guns.

GONZALES: Richard Aoki took his secrets to his grave. He was 71 and ill when he committed suicide in 2009. But before shooting himself, Aoki neatly laid out two sets of clothing: his freshly pressed Army uniform and a black leather jacket, black trousers and beret – his uniform as a Black Panther. Richard Gonzales, NPR News, San Francisco.

The images and message terrified J. Edgar Hoover, then the director of the FBI, who called the group “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” Hoover launched a covert campaign to undermine the Panthers.

Since the release of more FBI records from the time, a new question has come to the fore: Did the man who armed the Panthers work for the FBI?

DOCUMENTS: Richard Aoki’s FBI File

Founded in 1966, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense insisted that someone had to stand up to the police.

Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale called for “an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people.”