Fela Kuti: Chronicle of A Life Foretold

When Fela Anikulapo-Kuti died in August 1997, Nigeria lost one of its most controversial and inspirational cultural figures. Here, the Africa-based writer Lindsay Barrett maps the extraordinary trajectory of Fela’s life, detailing the emergence of his patented brand of Afrobeat, his anarchic lifestyle, and the ongoing battles with the Nigerian authorities. This feature was originally published in The Wire 169 (March 1998).

No one who knew him well was surprised when Nigeria’s greatest musician Fela Ransome-Kuti changed the first part of his double-barrelled surname to Anikulapo in the mid-1970s. He was just being consistent. Throughout his career, up to that point, Fela had constantly changed his mode of living and transformed the nature of his music. Eventually this process of change was to become the force that motivated his entire life.

The renaming was instructive. Anikulapo means ‘I have death in my pocket’, which is to say, as he often did, ‘I will be the master of my own destiny and will decide when it is time for death to take me’. When he died in August of last year at the age of 58, Fela appeared to fulfil the prophecy implicit in that earlier name change; and the manner of his dying was as dramatic and unruly as the manner of his living.

In the weeks leading up to his death, Fela’s condition deteriorated while he refused to accept treatment from Western-trained doctors, in spite of the fact that many of his family were illustrious medicos (Koye, the eldest, and former Minister of Health; Beko the younger, who was once President of the Nigerian Medical Association, detained incognito by the Nigerian government for his outspoken protests against what he believed to be the anti-democratic activities of the military; and his elder sister, a former matron in Nigeria’s health services). To the end Fela was a conscious rebel. The themes of his rebellion never changed, and the anarchy which often seemed to surround his life and music was always tempered by the fundamental truths which he sought to elucidate with regard to both African society and the ongoing exploitation of people in African nations.

Fela’s family wanted him to become a lawyer, and in 1958 he left Nigeria for the UK, ostensibly to study law. But many of his close friends maintain that he never intended to follow that line, and that he had made his decision to be a musician from his schooldays.

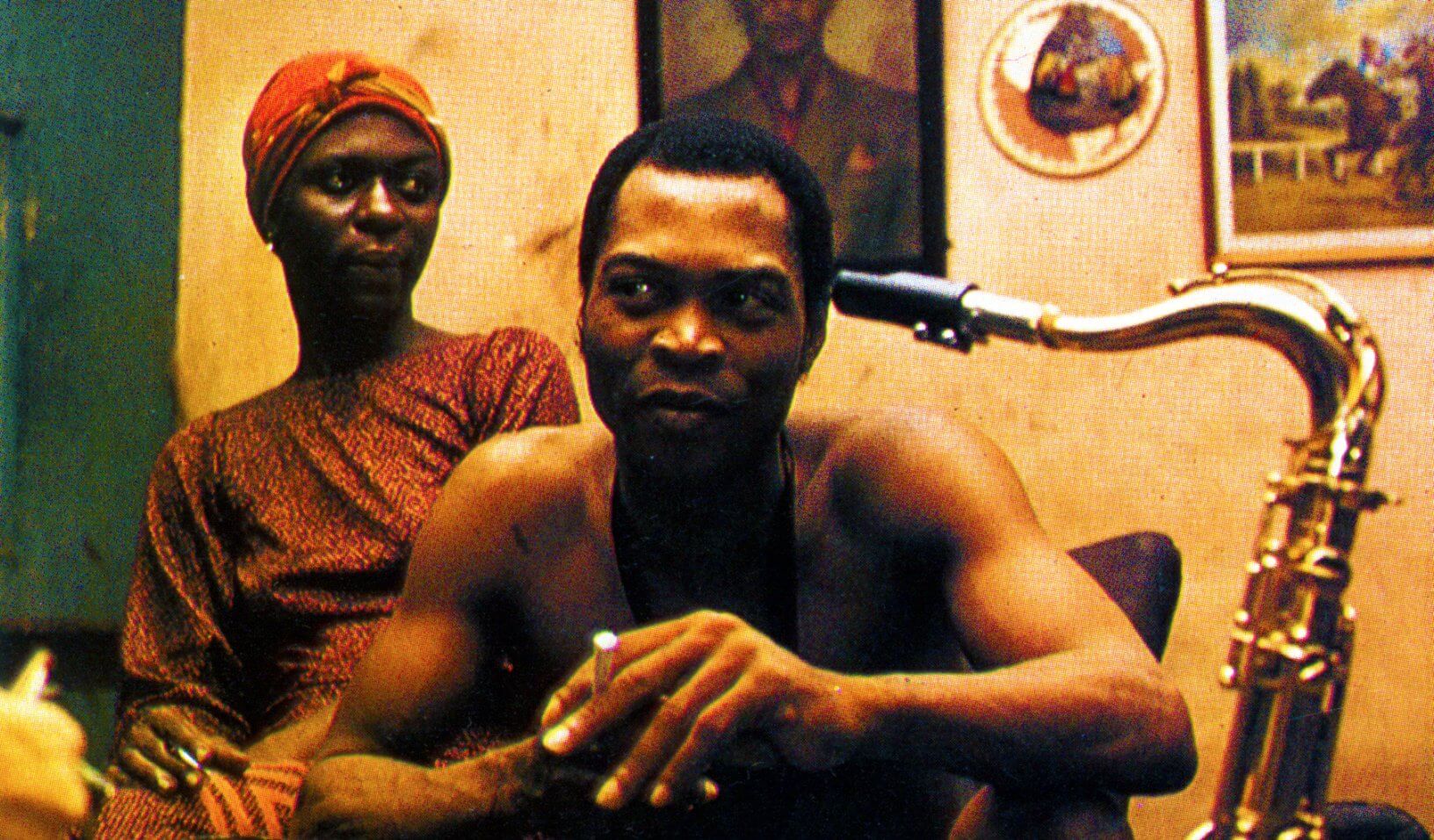

Once in the UK Fela enrolled In the Trinity School of Music. The trumpet was his preferred instrument, as most of Nigeria’s leading highlife band leaders were trumpeters and at least two of them, Rex Jim Lawson and Victor Olaiya, were early heroes of Fela’s. Although his father, the Reverend Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, encouraged him to play the piano, he had begun to practise the trumpet on his own before leaving secondary school, and sat in with many of the popular groups of the day. Bandleaders such as Roy Chicago, Bobby Benson, Eddie Okonta and the late anarchic genius Billy Friday all encouraged him and spoke highly of his youthful talent. However, Fela once told me that it was the discovery of Miles Davis’s early recordings with Charlie Parker that strengthened his commitment to the instrument when he began studying in London.

During his stay in London, Fela also listened to Afro-Cuban music, and began performing in venues frequented by African students and workers with a group of dedicated Nigerian musicians which included the pianist Wole Bucknor, who became the Musical Director of the Nigerian Navy Band, and the fine jazz drummer Bayo Martins. In fact Martins was a seminal influence on Fela’s listening habits, and was largely responsible for steering him in the direction he was eventually to take in building a close link between jazz and highlife music.

Fela returned to Nigeria in the mid-60s, and was employed by Nigeria’s National Broadcasting Corporation, but he seemed to have little interest in working there. He formed his first professional group, The Koala Lobitos, and in their earliest performances the musical influences which had exercised Fela’s imagination in the UK came to the fore. The group made some recordings, and while Fela’s trumpet playing, though lyrical, sounded weak in interpretative power, his singing was innovative, more discursive and rational than the general run of highlife vocalising of the time. Fela’s musical sensibility drew on the principles of West African popular music, especially its hypnotic, cyclical rhythm patterns, and he was always conscious of the ability of music to carry a social message in a powerful way. Accordingly, the lyrics he wrote for The Koala Lobitos also demonstrated a desire to bring new subjects into the purview of the music.

In 1968, by which time he had consolidated the membership of The Lobitos, new elements began to surface in the music which were strongly influenced by James Brown’s recordings. In that year Fela gave a number of press interviews claiming that Brown had actually “stolen my music”. Whatever the truth of the matter, what was clear was that in emphasising the rhythmic and improvisational elements, Fela’s music was drawing closer to the kind of extended trance-like workouts that defined Brown’s music of the period.

Later the same year, Fela went on a maverick tour to Ghana, the acknowledged home of highlife. He was accompanied and guided on the tour by Benson Idonije, a well-known Nigerian producer who was responsible for the presentation of jazz on Radio Nigeria. But while his music was well received by both Ghanaian audiences and musicians, he felt that in Nigeria his talents were still not appreciated. He either lost or left his job at the radio station after that. While still in Ghana he met a promoter called ‘Duke’, a Ghanaian who had relocated to California, and together they began to plan a tour to the USA.

The tour took place in 1969, and turned out to be a frustrating sequence of triumphs and disasters. It was halted when it was discovered that the promoter had not obtained the proper work permits for all the group’s members. In addition, some members absconded, and in a legal fight with some of the local promoters, Fela seized a collection of hired instruments and shipped them back to Nigeria. He left the USA under a cloud of debt and threats of legal action, but in the few months he had been there he also met many musicians and other artists, especially writers and painters, who were harnessing their creative energies to the kind of radical politics that were being espoused by groups such as the Black Panthers. It was on this trip that he realised how valuable an understanding of Africa’s history could be to the expansion of music’s outreach, and it was during this trip too that he was able to record some of his latest compositions with a new group of musicians who interpreted his musical vision with a greater level of commitment and ability. He called this group Nigeria 70.

On his return to Nigeria Fela renamed the group a second time, calling it Africa 70. He hired the Kakadu (Parrot) nightclub in Yaba, a suburb of Lagos, renamed it the Afro-Spot, and instigated a programme of three live sessions a week that were to produce some of the most extraordinary events in African musical history.

Liberated by the music’s new open-ended forms, some of the members of Africa 70 emerged as performing geniuses in their own right: tenor saxophonist Igo Chico Okwechime (replacing Isaac Olasugba), drummer Tony Allen, guitarist Fred Lawal and percussionist Henry ‘Perdido’ Kofi. Fela gradually dropped the trumpet and concentrated on leading the group by conducting it from the front and singing. Eventually his rudimentary keyboard riffs, which he used as part of his conducting formula, began to become more integral to the arrangements. By early 1971 he had stopped playing trumpet solos entirely and Tunde Williams, playing second trumpet, developed into a key player, taking over the important brass parts which Fela introduced into the arrangements.

By now Fela was virtually composing his songs in public. Each week at the Afro-Spot new works were premiered, and Fela would talk the audience through the meaning of the lyrics and work the group through the arrangement on stage. In this way classics such as “Lady”, “Go-Slow”, “Water No Get Enemy”, “Chop And Quench”, “Palava” and “Shakara-Oloje” emerged to become part of the urban folklore of Lagos. Not only were the songs massive local hits, but for many Lagos citizens it became imperative to attend these sessions, where Fela’s interactive style made the audience a part of the performance.

That year – 1970-71 – Fela set a pace which was incredible, not only in terms of his musical growth but also his philosophical and ideological trajectory. The issues he raised as he discussed the lyrics of his songs grew increasingly topical, and he began the form of public speaking which he termed ‘yabis’ in which he would excoriate government officials for their inefficiency, or preach a new form of freedom of expression which he equated with the right to smoke ‘igbo’ (marijuana). Before his trip to the USA, Fela had neither smoked nor drank. He was a serious and committed musician, definitely no libertine. Back in Lagos, he claimed that a young woman he had met in America (who was later to sing on one of his albums) had introduced him to marijuana, and he was now convinced that the use of stimulants was not taboo provided the user was ‘conscious’. This attitude was eventually to contribute greatly towards his many confrontations with the Nigerian government, and his public criticisms became increasingly focused on specific instances of what he considered to be government hypocrisy and the betrayal of national potential.

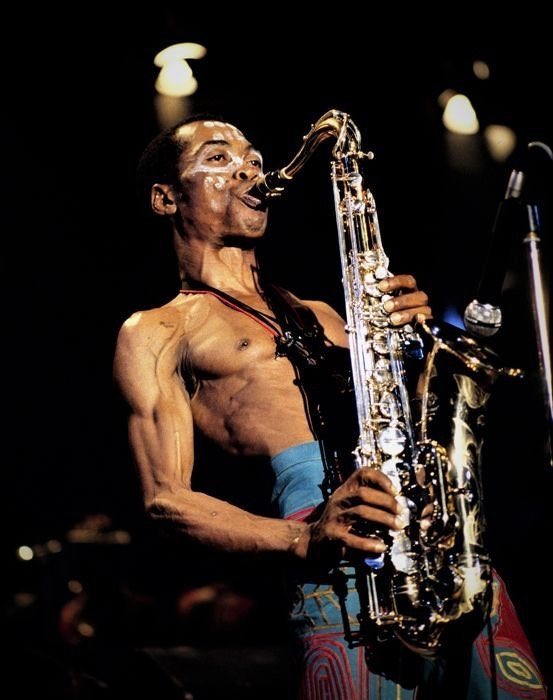

As his group grew from nine to 16 members, the music became less lyrical and more strident, the arrangements more complex. In 1974 Fela had a serious falling out with his tenor saxophonist Igo Chico, and in one of the legendary feats of his life, he vowed to replace Igo himself in 24 hours. According to the legend, Fela practised for 17 hours straight, and when the group appeared at the Afro-Spot that Friday night, he played all the famous Igo Chico tenor saxophone solos, not nearly as brilliantly as the master but with enough competence to satisfy his loyal audience.

This period also marked a turning point in Fela’s commercial strategies. He moved from the Afro-Spot to a new club located in another part of Lagos called Surulere. The club was owned by a legendary Lagos entrepreneur, Chief SB Bakare, and Fela began to operate a full week’s schedule. It was here that he first referred to his club as the Shrine, and began to speak of his musical existence as a religious rather than a purely commercial experience.

Fela’s recording strategy was a particularly unique one at this point. Almost monthly he would go into the EMI studios in Apapa and produce extended versions of two of the group’s most popular and topical compositions. EMI would release the songs immediately, their remarkable sales fuelled by the fact that a few weeks after they were issued on vinyl, Fela would stop singing them in his club. Fela continued this strategy for two years, issuing records like news bulletins, so that he served as a symbol of Nigeria’s united national consciousness, as his songs would be heard blaring from loudspeakers across Nigeria as soon as they were released. The fact that his lyrics were in a very direct form of pidgin English was crucial, as it made his records accessible throughout Nigeria and much of Anglophone Africa.

Now Fela decided to build his own management team and control the release and performance of his music himself. In the early 70s, multinational record companies such as EMI, Decca and Philips/Phonogram had a stranglehold on recording and management of groups in Nigeria and elsewhere in West Africa, bankrolling watered down versions of US soul and Fela’s patented Afrobeat. But as Fela developed into a megastar he sought to gain greater benefits from his recording contracts by encouraging competitive bidding among the rival companies for his independently recorded tapes.

The strain of this strategy caused cracks to appear within Fela’s own organisation. He tended to be informal and careless with his finances, and some of his musicians broke away when it became difficult for him to pay them regularly. This was the period too when he began to expand his team of female dancers and establish a commune in his mother’s house at Mosholashi-Idi-Oro. His sexual appetite was legendary, and many young women submitted themselves to a life of virtual enslavement as he preached an ideology of chauvinistic control and established a lifestyle that was based on his theories of female submission.

With the departure of certain musicians, the nature of the group changed drastically. Fela added more percussion and developed a new style of rhythm guitar voicing, laying a greater emphasis on the guitars and bass to carry the melody lines. He gave control of the reed and brass sections to Lekan ‘Ani’ Animashaun, a baritone saxophonist and one of the stalwarts of Fela’s music, and spent more time refining his keyboard playing. Along with the ensemble singing of his female chorus, these developments became the signatures of his music, and the most distinctive sound of Afrobeat emerged from this era.

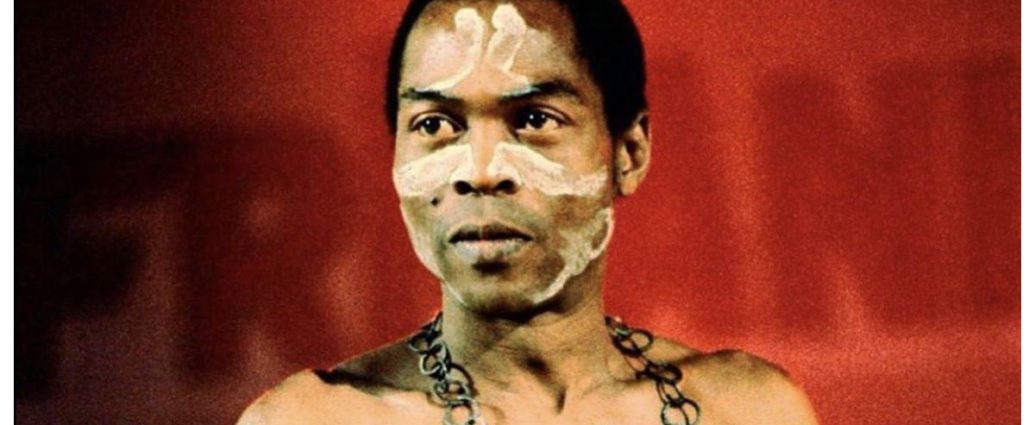

Some time In 1974, Fela moved from his Surulere base to the former Ambassador Club, a famous nightspot owned by the Lagos-based Ibo businessman and entertainment tycoon, Chief Kanu. This club was rechristened the African Shrine, and it was here that Fela began to incorporate ritualistic elements into his performances, including the pouring of libations and ceremonies performed by a succession of visiting traditional priests, some of whom appeared from nowhere, it seemed, and disappeared just as mysteriously. There was a Camerounian High Priest who, it was claimed, had sacrificed a human being at the Shrine and brought the victim back to life. Then there was a Ghanaian who performed magic tricks, and a Yoruba ‘Babalawo’ who gave Ifa divinations for selected members of the audience. Eventually Fela himself was declared High Priest of the Shrine, and each of his performances was prefaced with an elaborate ritual ceremony, replete with face painting, libation pouring, wild dancing and special prayers offered to the ubiquitous ‘God of Africa’.

The African Shrine was located right opposite his mother’s house, where his commune was still based, and his presence attracted a lot of commercial activity to the area, including a swarm of marijuana dealers. It was in this period, from 1974-76, that both his lifestyle and political attitudes coalesced into a flagrant challenge to the Nigerian authorities.

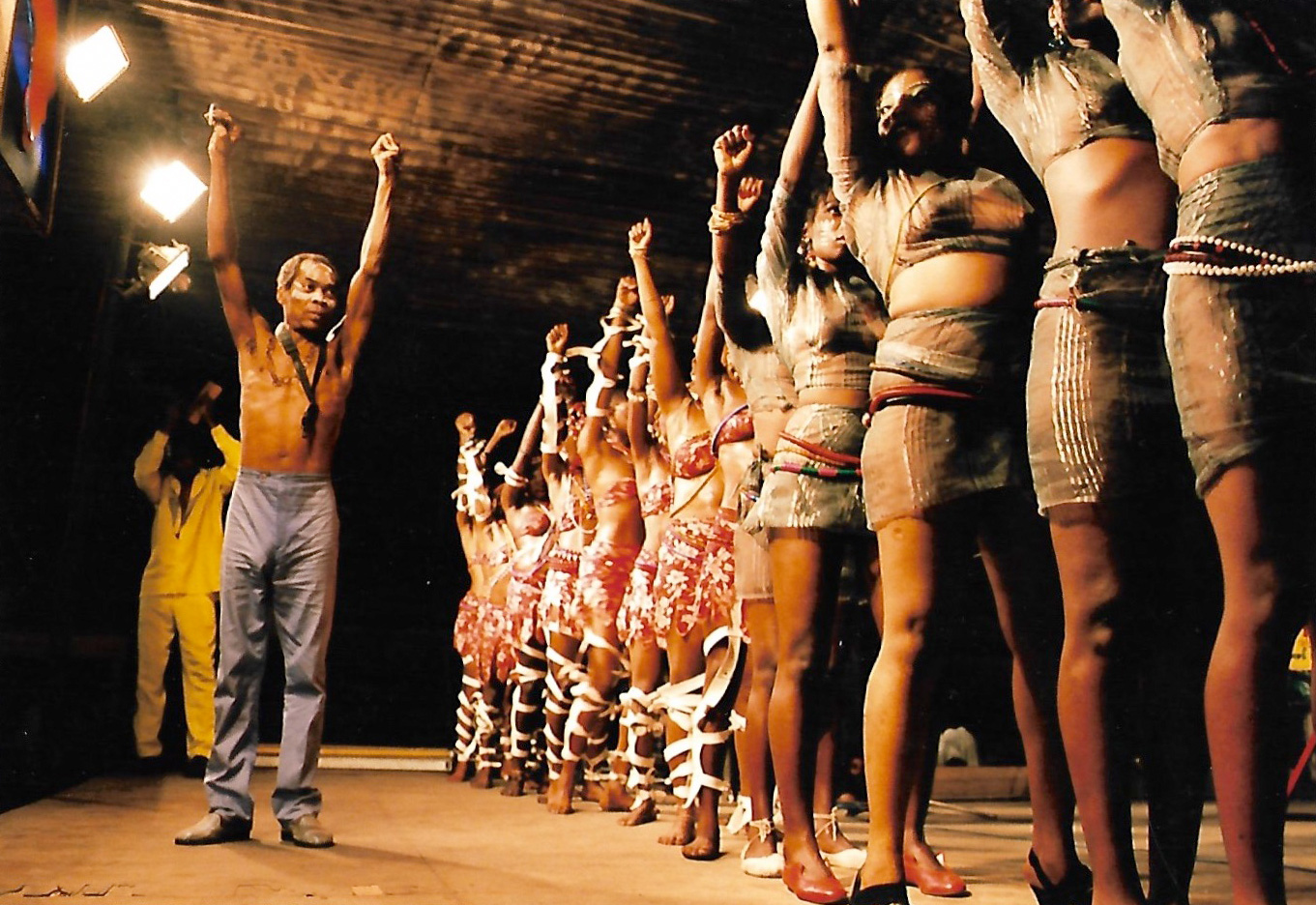

Apart from openly advocating the smoking of ‘igbo’ on the theory that “the God of Africa created this herb to enlighten his people”, he also paraded his harem of young women all over Lagos. For a while they were appendages to his entourage, but in mid-1975 he began to incorporate them into his show, first as dancers and then as members of the vocal chorus. Later that year he undertook the famous single-day traditional marriage in which he pledged himself as husband to 28 women.

There followed another change of name for the group. Fela had begun reading esoteric literature promoting the belief that African history had been distorted and misrepresented by Western academics, and his interpretation of these ideas and transformation of them into musical themes became his main concern. Reflecting this embrace of pan-African revisionism, he now called his group Egypt 80.

Fela began applying these radical ideas in a pungent and systematic criticism of the Nigerian Government’s own decrepit value system. Inevitably, the state began to fight back against both his political criticisms and what some government officials referred to as his ‘immoral’ lifestyle, and in what would turn out to be just the first of many raids on his club and commune, Fela’s house was raided in daylight by teams of soldiers and police.

During the raid Fela was arrested and taken to the notorious Alagbon Close jail, where he was hailed as a hero by the prisoners and installed as ‘president’ of one of the toughest cells, named after the infamous dark hole of Calcutta but pronounced ‘Kalakuta’. On his release he immortalised this experience in the extraordinary protest song “Kalakuta Show”, and renamed his commune the Kalakuta Republic. This marked a major turning point in his life, and in many ways may have sealed his fate.

Fela’s domestic lifestyle, and his battles with the Nigerian authorities, became major selling points for Nigerian tabloids. One newspaper, The Sunday Punch, serialised a set of features about the Kalakuta experience, liberally sprinkled with pungent quotes from Fela himself, and sold in numbers hitherto unknown for independent newspapers in Nigeria. His reputation also began to spread abroad: The New York Times ran a major feature on him, and his comments began to surface in foreign articles surveying Nigeria’s economic and political climates. It is a moot point whether this attention was responsible for his increasing militancy or whether it was the other way round. Whatever the cause, Fela’s radicalism increased and his music became even more powerful as a result. The consistency with which he interpreted political events and issues in musical terms was remarkable. The anti-military pieces “Zombie” and “Unknown Soldier” were seminal products of this period. They indicated that Fela was unbowed in the face of sustained attacks from the police and military.

Eventually he fell out seriously with his record companies and began to attack them also. It was clear to Fela that the government had been putting pressure on these organisations to undermine his independence, and he set out to prove that he could survive without them. One of his most famous songs emerged during this period, “ITT” (“International T’ief T’ief”), in which he heaped abuse on Chief MKO Abiola who was then ‘Vice President for Africa and the Middle East of ITT’, owners of the Decca label.

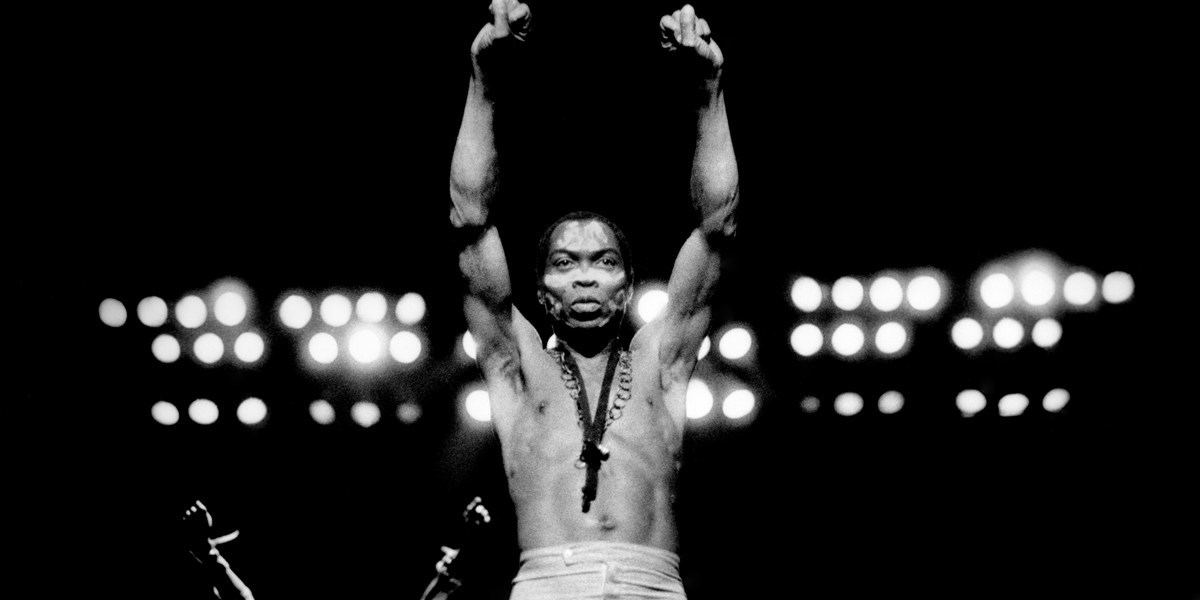

In a further break from the conventions of the record industry, some of Fela’s closest friends were drafted into his organisation to handle contractual and promotional matters. These included the late Kanmi ‘People’s Lawyer’ Osobu, Alhaji UK Buraimoh, the late Akin Davies and Barrister ‘Wole ‘Feelings Lawyer’ Kuboye. Now Fela began to tour Nigeria playing concerts that drew up to 50,000 people at a time in places such as Port Harcourt, Aba, Benin City, Warri, Enugu, Jos, Kaduna and Calabar. These were not club dates but fully fledged stadium concerts. This strategy, and Fela’s increasing popularity, seemed to anger the government even more, and towards the end of 1976, after Fela had returned to Lagos following one of his major national tours, one of the most vicious attacks on his home took place.

The timing of the raid was strategic. Nigeria was about to host the Second World Festival of Black and African Arts (FESTAC 77), and the government obviously wanted to silence Fela before the expected large contingent of international visitors arrived in Lagos for the festival. If this was the intention, it backfired badly. The raid was covered widely in the media, and the songs Fela wrote by way of response emerged as some of his most popular international hits. In fact, during the festival the African Shrine was packed almost every night, proving more popular than any of the official FESTAC events, so much so that most nights Fela and Egypt 80 had to play four shows instead of the normal one or two.

In early 1978, a few months after FESTAC, Fela’s home was raided again, and this time the raid was carried out entirely by the military – with tragic consequences. Fela believed that the raid had been ordered personally by the then Head of State General Olusegun Obasanjo, a fellow Ogun State indigene, who had been humiliated by the amount of attention Fela had received during FESTAC. During the raid, Fela’s mother, Funmilayo, who was then around 75 years old, was thrown from a first floor window by “an unknown soldier”. In addition, Funmilayo’s house, and an adjoining clinic belonging to Dr Beko Ransome-Kuti, were both burned to the ground. Official explanations for the raid were cynically off hand, which angered Fela even more.

When his mother died some months later from complications arising from the injuries she had received during the raid, Fela led a protest march carrying a coffin to the official residence of the Head of State in central Lagos, and also wrote one of his most tragic hits, “Unknown Soldier”, which contained the heart-rending lamentation, “Dem kill my mama, political mama, the only Mama in Africa”.

Shortly after the death of Funmilayo, Fela and his group went on a European tour, where he was surprised to discover that he had a massive following, especially in France. He toured for about three months, but on his return to Nigeria some of the key members of Egypt 80 – percussionist Henry ‘Perdido’ Kofi and drummer Tony Allen – left the group. In addition, one of its brighter young stars, the guitarist Kologbo, absconded and remained in Europe. The European tour was a success both critically and commercially, but once again Fela’s casual approach to finance led to disagreements within the group. Moreover, he seemed increasingly depressed over the death of his mother.

Although he had never been a big drinker Fela had created a special compound which he called ‘Felagoro’ made from marijuana mixed with the local gin ‘ogogoro’, and he used it extensively during the European tour. The compound was a powerful hallucinogenic and sometimes, when under its influence, his performances were erratic, and the music was mostly held together by Lekan ‘Ani’ Animashaun, who had developed into a powerful baritone saxophonist, and was officially designated musical director of the group.

During the European tour Fela introduced his teenage son Femi on stage in the heat of a hard-driving performance in a circus tent outside of Paris. It was a real baptism of fire, as Femi was breaking in a new alto saxophone, and previously had only practised with the group during rehearsals. But before a crowd of more than 10,000 Fela ordered Femi to take his first major solo. Fela stood by the side of the stage driving his son on with shouts of encouragement and derision. The experience proved its worth. Femi now leads a group called Positive Force, and has developed a streak of determination in almost direct response to his father’s unorthodox method of apprenticeship.

After his return from Europe, Fela’s life and music took on a doomed brilliance which was overshadowed by a cloud of inevitable confrontation. Raids by the police and military became even more regular when he moved to Ikeja and took over another club, where he installed the New African Shrine. His hangers-on from Mosholashi-Idi-Oro followed. They virtually repopulated the area around the Shrine bringing hard drugs, especially ‘bana’ (heroin) and crack, with them. Fela spoke against the use of any drugs other than igbo, but many members of his entourage, including some of his wives, had already become junkies, a development which only seemed to reinforce the allegations of immorality and criminality that the government was levelling against him.

The confrontation between Fela and the security forces now developed into one of the saddest displays of state terrorism ever seen in Africa; sometimes it appeared that individual government members and departments were vying with each other to see which one was more anti-Fela.

In 1983 Fela announced that he would be standing for President in the forthcoming Nigerian elections on the ticket of his own party, the Movement of the People (MOP), in order to “clean up society like a mop”. Following the elections, the military overthrew the new civilian government and the attacks on Fela increased again. He was accused by one agency of flouting the country’s currency laws because he returned from an overseas visit with about 1000 US dollars. He was arrested, charged, and kept in detention for almost two years. He was released in 1986 after yet another coup had occurred, but just a few months later he was charged with kidnapping one of the young women who lived at his house and whose father was said to be a senior official in one of the security agencies. Fela was acquitted, but a year or so later he was accused of murder after someone had been killed in a fight at the Shrine. Years later, Fela told me that he believed the dead man was killed and planted in the club by yet another branch of the security services.

Even during this incredibly fraught period, Fela’s music retained an innovative strength. Just before the breakdown of apartheid in South Africa at the beginning of the 1990s he began to turn his attention to the subject of world racism, and the economic exploitation and international hypocrisy that sustained it.

His composition “Beast Of No Nation” evolved out of a statement by South Africa’s President PW Botha: “This uprising [against the apartheid system] will bring out the beast in us.” The song was powerfully argued and the music showed that Fela had not lost his sense of rhythmic vitality in his approach to composition. Many of his last songs written between 1993-96 represent some of his best work, containing large scale orchestrated arrangements with more freedom for melodic interpretation. In a parallel with the increased sophistication of his music, Fela announced that marriage was an erroneous imposition of control on a fellow human being. Accordingly, he granted freedom to all his wives, or at least those who remained – more than half of the original 28 had already absconded, although many of them remained resident in his house and as members of his performing ensemble.

Even as Fela was revising his lifestyle, the authorities were closing in. A few weeks before his death, his health shot to pieces by years of official and personal physical abuse, he was paraded in chains on state television in Lagos by yet another security agency, the Anti-Drug Squad. Even in these harrowing circumstances, Fela maintained his dignity, challenging the director of the agency openly, and declaring that he did smoke marijuana and considered it not only his right but a privilege ordained for humanity by the “God of Africa”.

By now, Fela’s poor health was obvious. He was skeletal, but his spirit was unbowed. He continued to appear at the Shrine, and whenever the group, led by Lekan Animashaun, struck up its signature tunes, he still found the strength to leap on stage and blast his adversaries and proclaim his belief in the rejuvenative power of his personal vision. To the end, Fela believed that this vision was motivated by a spiritual link to the ancestral power of Africa, and that even if it did not save his own life it had the power to restore a sense of political renewal in the continent.

Fela died on 2 August 1997. Some members of his family announced that he was suffering from AIDS, and have demanded that the Nigerian government establish a campaign to officially recognise the AIDS issue as a potentially catastrophic one for the whole of Africa. In this way they probably hope that Fela’s death might help bring about the kind of fundamental changes in Nigerian society which he strived for during his life, but failed to achieve, in spite of his constant battles with officialdom.

Fela’s funeral developed into a festival of joy and anger unprecedented in Lagos. Three days of processions culminated in a public service which brought the city of well over five million people to a standstill – obviously, Fela’s spirit still ran deep in the hearts of the masses.

It is no exaggeration to say that Fela’s memory will always symbolise the spirit of truth for a vast number of struggling people in Africa and beyond. His music and the determined consistency with which he challenged authority and demanded that popular ambitions and attitudes should be reflected in the official objectives of the nation’s leadership will continue to create a basis for radical challenges to the complacency of officialdom. His musical legacy is a solid one. His compositions are effectively underscored by the huge number of records which he leaves behind. Everyone who worked with him retained a deep sense of his musical spirit, and in the future, his formal musical legacy will grow even stronger as the extraneous elements of his wild, anarchic lifestyle give way to reflective tributes to his talent and the philosophical relevance of his ideas.

The members of Fela’s group, devastated by his passing, will find it difficult to keep the flame alive, but there is also a need to preserve the traditions which Fela established. One of his greatest legacies is the consummate technical proficiency which he enabled his instrumentalists to achieve even without travelling beyond Nigeria. Some of his soloists, such as the young baritone saxophonist ‘Showboy’ and the leader Lekan Animashaun, have the breadth of experience as well as the evanescent quality of stardom in their veins.

Now that he is no longer alive, the eternal values which gave birth to Fela’s perpetual struggle to find justice in life will gain new strength through the immortal power of his musical vision.

Copyright © Lindsay Barrett 1998.