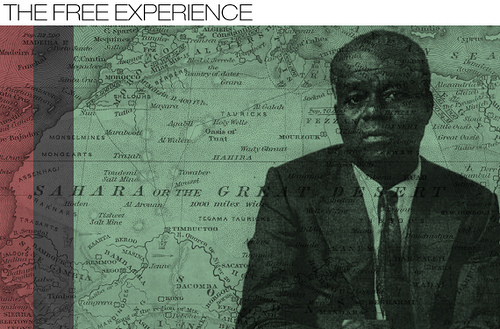

| DR. JOHN HENRIK CLARKE — JANUARY 1, 1915 – JULY 16, 1998″A good teacher, like a good entertainer first must hold his audience’s attention, then he can teach his lesson.” ~John Henrik Clarke |

“I saw no African people in the printed and illustrated Sunday school lessons. I began to suspect at this early age that someone had distorted the image of my people. My long search for the true history of African people the world over began.”

Dr. John Henrik Clarke

“My main point here is that if you are the child of God and God is a part of you, the in your imagination God suppose to look like you. And when you accept a picture of the deity assigned to you by another people, you become the spiritual prisoners of that other people.”

Dr. John Henrik Clarke

“Powerful people cannot afford to educate the people that they oppress, because once you are truly educated, you will not ask for power. You will take it.”

Dr. John Henrik Clarke

“Religion is the organization of spirituality into something that became the hand maiden of conquerors. Nearly all religions were brought to people and imposed on people by conquerors, and used as the framework to control their minds.

Dr. John Henrik Clarke”

“If God lives in you, then you have the obligation to walk the earth as a God.”

Dr. John Henrik Clarke ”

“Dr. John Henrik Clarke was born January 1, 1915 in Union Springs, Alabama and died July 16, 1998 in New York City. His mother, Willie Ella Mays Clark, was a washerwoman who did laundry for $3 a week. His father was a sharecropper. As a youngster Clark caddied for Dwight Eisenhower and Omar Bradley “long before they became Generals or President,” Clarke recalls in describing his upbringing in rural Alabama.

Clarke was inspired by his third grade teacher, Ms. Harris, who “convinced me that one day I would be a writer.” But before he became a writer he became a voracious reader. Inspired by Richard Wright’s Black Boy, Clarke went to New York via Chicago. He enlisted in the army and earned the rank of Master Sergeant. After mustering out, Clarke moved to Harlem and committed himself to a lifelong pursuit of factual knowledge about the history of his people and creative application of that knowledge.

Over the years, Clarke became both a major historian and a man of letters. Although he is probably better known as a historian, his literary accomplishments were also significant. He wrote over two hundred short stories. “The Boy Who Painted Christ Black” is his best known short story. Clarke edited numerous literary and historical anthologies including American Negro Short Stories (1966), an anthology which included nineteenth century writing from writers such as Paul Laurence Dunbar and Charles Waddell Chestnut, and continued up through the early sixties with writers such as LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) and William Melvin Kelley. This is one of the classic collections of Black fiction.

Reflective of his commitment to his adopted home, Clarke also edited Harlem, A Community in Transition and Harlem, U.S.A. Never one to shy away from the difficult or the controversial, Clarke edited anthologies on Malcolm X and a major collection of essays decrying William Styron’s “portrait” of Nat Turner as a conflicted individual who had a love/hate platonic and sexually-fantasized relationship with Whites. In both cases, Clarke’s work was in defense of the dignity and pride of his beloved Black community rather than an attack on Whites. What is significant is that Clarke did the necessary and tedious organizing work to bring these volumes into existence and thereby offer an alternative outlook from the dominant mainstream views on Malcolm X and Nat Turner, both of whom were often characterized as militant hate mongers. Clarke understood the necessity for us to affirm our belief in and respect for radical leaders such as Malcolm X and Nat Turner. It is interesting to note that Clarke’s work was never simply focused on investigating history as the past, he also was proactively involved with history in the making.

As a historian Clarke also edited a book on Marcus Garvey and edited Africa, Lost and Found (with Richard Moore and Keith Baird) and African People at the Crossroads, two seminal historical works widely used in History and African American Studies disciplines on college and university campuses. Through the United Nations he published monographs on Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois. As an activist-historian he produced the monograph Christopher Columbus and the African Holocaust. His most recently published book was Who Betrayed the African Revolution?

In the form of edited books, monographs, major essays and book introductions, John Henrik Clarke produced well over forty major historical and literary documents. Rarely, if ever, has one man delivered so much quality and inspiring literature. Moreover, John Henrik Clarke was also an inquisitive student who became a master teacher.

During his early years in Harlem, Clarke made the most of the rare opportunities to be mentored by many of the great 20th century Black historians and bibliophile. Clarke studied under and learned from men such as Arthur Schomburg, William Leo Hansberry, John G. Jackson, Paul Robeson, Willis Huggins and Charles Seiffert, all of whom, sometimes quietly behind the scenes and other times publicly in the national and international spotlight, were significant movers and shakers, theoreticians and shapers of Black intellectual and social life in the 20th century.

From the sixties on, John Henrik Clarke stepped up and delivered the full weight of his own intellectual brilliance and social commitment to the ongoing struggle for Black liberation and development. Clarke became a stalwart member and hard worker in (and sometimes co-founder of) organizations such as The Harlem Writers Guild, Presence Africaine, African Heritage Studies Association, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, the National Council of Black Studies and the Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations.

Formally, Clarke lectured and held professorships at universities worldwide. His longer and most influential tenures were at the Africana Studies and Research Center at Cornell in Ithaca, New York, and in African and Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College in New York City. He received honorary degrees from numerous institutions and served as consultant and advisor to African and Caribbean heads of state. In 1997 he was the subject of a major documentary directed by the noted filmmaker Saint Claire Bourne and underwritten by the Hollywood star Westley Snipes.

John Henrik Clarke is in many ways exemplary of the American ethos of the self-made man. Indicative of this characteristic is the fact that Clarke changed his given name of John Henry Clark to reflect his aspirations. In an obituary he penned for himself shortly before his death, John Henrik Clarke noted “little black Alabama boys were not fully licensed to imagine themselves as conduits of social and political change. …they called me ‘bubba’ and because I had the mind to do so, I decided to add the ‘e’ to the family name ‘Clark’ and change the spelling of ‘Henry’ to ‘Henrik,’ after the Scandinavian rebel playwright, Henrik Ibsen. I like his spunk and the social issues he addressed in ‘A Doll’s House.’ …My daddy wanted me to be a farmer; feel the smoothness of Alabama clay and become one of the first blacks in my town to own land. But, I was worried about my history being caked with that southern clay and I subscribed to a different kind of teaching and learning in my bones and in my spirit.”

Body and soul, John Henrik Clarke was a true champion of Black people. He bequeathed us a magnificent legacy of accomplishment and inspiration borne out of the earnest commitment of one irrepressible young man to make a difference in the daily and historical lives of his people. Viva, John Henrik Clarke!” — V♥-♥<1>♥

Peace, Love and Blessings!