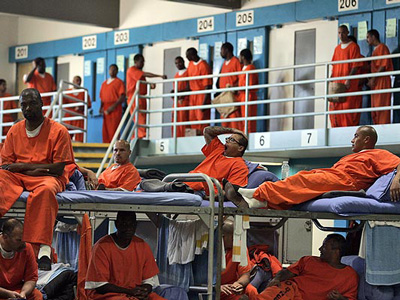

The U.S. Supreme Court ruling Monday ordering California to release nearly 40,000 of its 143,435 inmates has the state in a panic as officials scramble to figure out what happens next.

The SCOTUS ruling affirmed a lower court order that required California to reduce its inmate population to 137% capacity, or about 1,100 inmates. The state’s prisons are now at about 180% capacity and in recent years have operated at up to 200% capacity.

California now has to come up with a plan to cut its prison population by a quarter over the next two years – a massive bureaucratic feat that has the potential to cause real problems for public safety. Here’s what you need to know:

WHY ARE CALIFORNIA’S PRISONS SO CROWDED?

A lot of California’s overcrowding problem is the result of the state’s punitive “three strikes law,” which puts third time offenders in jail for life, regardless of their crime. Georgetown Law professor David Cole writes in the New York Review of Books notes that prison population growth can also be attributed to a dramatic increase in prosecution and incarceration for drug offenses over the past three decades.

Andrew Cohen at The Atlantic notes that the problem is simple: “You send seven times more state inmates to prison for committing a wider range of crimes, and you fail to build seven times more prisons to hold them, and pretty soon you have a problem.”

WHAT HAPPENS NOW?

California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) has proposed a “realignment” plan that would avoid releasing any inmates by shifting low-level offenders to county facilities. It would also reduce parole supervision and stop sending parolees back to prison on ‘technical violations.’

The state legislature has already approved the plan but not the funding that would pay for it. The plan would cost hundreds of millions to be paid for with tax hikes that Republicans have so far refused to pass.

Counties say that they have the capacity to house the extra inmates but not without help from the state.

“The only logical way to deal with the court order in a manner that continues to protect the public is to send some people to the counties,” Paul McIntosh, executive director of the California State Association of Counties, told the NYT. “A one-time release would be a terrible decision, and we need a fundamental change in the way we deal with criminals. The state really needs to step up quickly to give us the ability to deal with this.”

If there is no money for Brown’s realignment strategy, the state will have to come up with a totally different plan. So far, however, there are no other proposals on the table.

California’s Corrections Secretary Matthew Cate said today that the state is looking to increase transfers to out-of-state prisons. Another option is building new facilities, but in light of California’s fiscal struggles, it is unlikely the state can build itself out of its prison crisis.

In the end, Cate said, the state may have to reduce sentences for low-level, non-violent criminals.

WHY CALIFORNIA’S PRISON CRISIS COULD BE A HUGE PROBLEM:

Whether the inmates are transferred to county jails or released early, the wave of inmates could wreak havoc on local law enforcement and communities. LAPD Chief Charlie Beck has said that the state prison release will be the biggest challenge he will ever face as the city’s top cop.

One potential threat is the spread of California’s prison gangs, many of which have extensive outside criminal networks and drug trafficking operations. Releasing these prisoners or moving them to county jails could allow these gangs to establish deeper ties at the local level and facilitate access to the outside.

Even transferring members incarcerated for non-violent crimes runs the risk of further entrenching the gangs in California’s criminal justice system. The results could be catastrophic for public safety officers unequipped to deal with the threat.

Grace Wyler

Nothing here is by chance. A plan intended to fail. What do they expect?